As joyful as a saz

And sad, we start all days

And as warm as a folk song

We know that the dawn that will wrap the chest of the mountains

And set them in motion

Shall begin with those who defend dignity in the darkness

With the language of light...

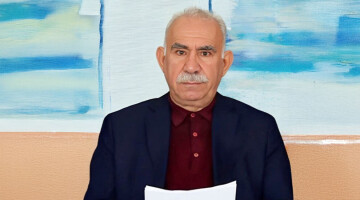

These lines are by the poet Adnan Yücel. Our friend and fellow journalist Seyit Evran, whom we lost on 22 September, met the Kurdish poet Adnan Yücel from Elazığ at Çukurova University. He attended several lectures by Adnan Yücel when he was a student there. Seyit liked Adnan Yücel and his poems very much and referred to them constantly.

Seyit Evran met many valuable people there. Among them, of course, was the immortal revolutionary Gurbetelli Ersöz. When Seyit Evran started studying at Çukurova University, Gurbetelli Ersöz, a graduate of the Chemistry Department, was working as a research assistant in the "Environment and Energy" department at the same university. It was here that Gurbetelli was arrested and imprisoned in 1989. Gurbetelli was released from prison in 1993 and began working as the editor-in-chief of the Özgür Gündem newspaper. In the meantime, Seyit Evran had graduated and returned to his hometown as a young political person. Seyit started working as a journalist at the same newspaper without interruption. Then the newspaper was bombed. When she could no longer work as a journalist because of the state attacks, Gurbetelli took to the mountains in 1995, of which she said, "I embroidered my heart in the mountains". Seyit Evran and many others did the same. Gurbetelli Ersöz was murdered in a KDP ambush in Gare on 7 October 1997. Seyit Evran and his friends heard this news on the radio one autumn day in the mountains of Amed.

Seyit's journey continued. In 1999, he went to South Kurdistan and actively continued his journalistic work for several years. In between, he also spent some time in Russia and the former Soviet countries, where he did great work. Through Seyit's reporting we learned a lot about the present and past of the Soviet Kurds. The last time I spoke to him about these issues, he mentioned a Kurdish tribe that had emigrated from the Caucasus to China. He had heard about it twenty years earlier, and he was still pursuing this topic. He could not go in search of these Kurds because he had neither the time nor the means. I hope that one of us will complete this story that Seyit left behind.

The first time I met Seyit Evran was in 2008 in the Bradost region. At that time, we were working for Roj TV and had gone to Bashur (South Kurdistan) to film a series of programmes. We stayed together for about a month and travelled around together. Seyit had already had a very long and exhausting journey. On his back he carried the memories of many people who had lost their lives in the Kurdish freedom struggle. He kept writing them down, recounting them and doing his best not to let them be forgotten. In fact, Seyit Evran was part of a team that compiled the memories and notebooks of hundreds of members of the guerrillas who had taken part and died in the freedom struggle into a four-volume book. For days and months, they travelled step by step through the mountains and plains, listening to thousands of people, sharing their memories and immortalising them. Seyit was the most prominent member of this team.

When the civil war broke out in Syria in 2011, Seyit turned his attention to the region and went to Rojava. He moved to the area around Afrin and Aleppo and provided the Free Kurdish Media with information about what was happening in Syria. While others interpreted the war in Syria with general information, Seyit was there in person and shed light on our understanding of the situation there. For example, he explained in detail the organisation of the jihadist structures in Syria, the local and regional relations and who is in contact with whom for what purpose. He never forgot information that he learned and confirmed. In analysing these groups, he sometimes went into astonishing detail. Above all, he was one of the first journalists to recognise and publicise Turkey's systematic relations with these jihadist groups.

Seyit Evran reported not only on political and military developments in the region, but also on social, societal and cultural issues. In keeping with his character, he worked on society-related topics. With hundreds of news stories and articles he wrote in Afrin, Aleppo and Shehba, he helped us to get to know the region better. Seyit Evran was also the first journalist to photograph the grave of Dr. Nuri Dersimi in the Shera district of Afrin and report on it in detail.

After Afrin, he worked in the Cizîrê region of Rojava. In 2016, when I worked at ANF, we spent a lot of time together here again. In the same year, it was Seyit who first took me to Shengal with our colleague Doğan Çetin. He had been there many times before, and when we travelled together, he knew all the roads and relations. Shengal was going through difficult times at that time. Operations against ISIS were taking place. During this time, our colleague Nûjiyan Erhan was also working in Shengal. Shortly after we returned, Seyit Evran gave us some bitter news: Nûjiyan had been killed in an attack by the armed KDP forces.

Seyit came to Bashur after a while. I worked at ANF headquarters and Seyit Evran took over responsibility for ANF there. We worked together for months in the ANF offices in Kirkuk and Sulaymaniyah. Seyit continued his work here until 2021. Our friend Karwan Horamî, who coordinated ANF's Persian service, and Seyit Evran were in the same working environment. Karwan also had a heart problem and they constantly criticised each other for not taking care of their health. The camaraderie between Karwan Hewraman and Seyit Evran was truly exemplary. Unfortunately, Karwan also passed away five months ago, and I cannot put into words how sad Seyit was about it.

Seyit Evran's journalistic work in Rojava and Bashur was unprecedented. It is not easy to compile news on every topic and from every environment while maintaining one's ideological-political course. Such journalism is difficult in the Middle East and especially in Kurdistan. Seyit is a rare journalist who has succeeded in this. He knew what line he was taking in his work and this attitude evoked admiration from all.

Seyit Evran left his mark as a revolutionary, intellectual journalist. He lived life to the fullest. He lived through thousands of hardships. He walked over mountains, rivers, mined borders and crossed brutal armies. He stood up for hundreds of journalists who were trained to work in the free Kurdish media, shared his experiences with them and was a role model for them. He witnessed great pain, destruction and loss. None of this deterred him. He was a comrade of those who wrote epics against barbarism and recorded their lives. It is impossible to imagine the Kurdish media without Seyit. But the Kurdish media will not be without Seyit Evran. Just like Gurbetelli Ersöz, Halil Dağ, Mehmet Şenol, Nûjiyan Erhan, Deniz Fırat and many others, Seyit Evran will always be among us and guide us.