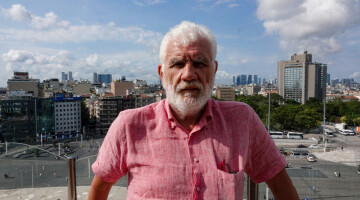

Refaat Alareer was born in 1979 in Gaza Strip, Shujaya. He was killed in an Israeli bombing targeting his sister's house in Gaza.

We interviewed Alareer a few years ago. He was born and raised under occupation, which means, as he said, that “every move I took and every decision I made were influenced (usually negatively) by the Israeli occupation”.

He finished my BA in English language and literature from the Islamic University-Gaza in 2001, and his MA in Comparative Literature from University College London (UCL) in 2007.

He lives in Gaza with his wife and 6 kids. He teaches world literature and creative writing at the Islamic University-Gaza.

“As a kid, - he said - I grew up throwing stones at Israeli military Jeeps, flying kites, and reading”.

When did you begin writing? Tell us the first memory you have of you writing?

I started writing in English during Israel’s 2008 offensive on Gaza that left about 1400 Palestinians dead. I still remember how I felt obliged to write back in English to reach out to the world to educate people about Palestine and save them from the dominant Israeli multi-million dollar campaigns of misinformation. The first real piece was a short sarcastic piece imitating Jonathan Swift’s “A Modest Proposal” in which I suggested instead of murdering Palestinian kids, Israelis should eat them up for their nutritious values and at the same time rid themselves of the so-called Palestinain demographic threat. But later, my writing was ignited while I was teaching comparative literature and creative writing to my students. Social media such as blogging and twitter made writing a daily practice, albeit in the form of very laconic posts and tweets.

Were you a reader in your youth? What was your relation with books when you were a child? Were books available?

As a kid growing up in the first Intifada, books were a luxury we could not afford. We grew up attending wedding parties and listening to Palestinian folk songs and resistance songs. That was the major source of education on Palestine. Other sources of reading were Palestinian factions press releases and graffiti. When at night young masked Palestinians sprayed the walls with graffiti, we could not wait for the day to break so we go around and read again and again every single word of that. Reading these was an act of resistance. It was the least, we kids, could do, besides throwing stones at the military Jeeps.

Having books on Palestine and resistance was a crime punishable by the Israeli occupation. I remember my elder brother and I had an Intifada poetry book. I used to read it with the doors and the windows shut. I never told anyone we had that book at home. It was like I was hiding a bomb. If we had been caught with such materials or with a Palestinians flag or a poster of Yassir Arafat, we might have ended up spending 6 months in Israeli prisons, or, worse, our father’s work permit would have been suspended.

School books were ok, but they did not help us understand what was going on. In Gaza, we had to use Egypt’s school books. And all references to Palestine were censored and erased by the Israeli occupation authorities. Whole pages and paragraphs were blank. That was where Palestine existed.

Let’s talk about your own work. What have you published so far?

I edited and contributed to “Gaza Writes Back”, a collection of short fiction written in English by 15 Young Palestinians living in Gaza. I also co-edited “Gaza Unsilenced”, which is a book of articles on Israel’s 2014 offensive on Gaza that killed about 2400 Palestinians. I also published a journal article entitled “Gaza Writes Back: Narrating Palestine”. I have a bunch of unpublished poems and other stories I am hoping to bring to the light soon.

Is there a distribution for your work both inside and outside of Palestine?

“Gaza Writes Back” is now in 7 languages. The book was published by Just World Books, a small, but influential, publisher in the United States. They do all the distribution to the English edition.

When I am done with my PhD, I am hoping I will invest more time and efforts into writing fiction and poetry. I have few unfinished texts that I am hoping to bring out to the world.

Which of your books/stories have been published in other languages?

“Gaza Writes Back” is in English, Italian, Turkish, Malay, Bengali, Persian, and (partly) Japanese. I had one of my poems translated (online) into Spanish.

https://thisisgaza.wordpress.com/2014/09/04/spanish-translation-of-my-poem-i-am-you-soy-vos/

What is your feeling on translation?

Translation is the best thing that happened to humanity. Translation breaks barriers and builds bridges and creates understanding. But “bad” translations could also create misunderstandings. And as much as I believe, and love, translation, I also believe that we need to train ourselves to express our concerns in the target language, here English. As Palestinians, there is good material that is translated into English and other languages, and there are people who speak for Palestinians in other languages. This is a two-fold weapon because we have always seen how mainstream media especially in the West mispresents Palestine by adopting the Israeli military discourse, terminology, and ideology. Translation here is dangerous and misleading.

Therefore, as an academic in an occupied land, major concern is to train as many people as possible to write effectively in English so that they express themselves in the way, discourse, and method they see fit, and hence overcome the dilemmas of translation.

In a word, we, Palestinians, need to translate Palestine. And Palestinians who are able to speak for themselves in other languages should to that directly.

Personally, I’d love to be part of a project to translate Palestinian folklore into English. This popular literature closer to the reality of Palestine and better represents the depth and richness of Palestinian culture and heritage.

Tell us a bit about your literary, musical, cinema influences...

In general, I love English poetry (my PhD is on John Donne’s poetry). I read Shakespeare. But I also love to read Russian, Italian, South American, and African Literature. I love reading literature by native peoples in America, Canada, Australia … etc. I have been influenced by Shakespeare, John Donne, Laurence Stern, Aphra Behn, George Eliot, T. S. Eliot, and Aphra Behn. I have some interest in Israeli and Hebrew literature and hope to develop this interest soon. Currently, my interest is mainly in emerging young artists and how they react to mainstream trends that try to silence them or render them irrelevant or immature.

I listen to classical Arabic music and resistance folklore especially Palestinian nasheed. I listen to some American country music.

I usually love a movie that was originally a book. I love movies with plot twists, or sub-plots. I also use them in my teaching. My Top movies include “Apocalypto”, “Death Sentence”, “First Blood”, “Room”, “No Country for Old Men”, “There Will Be Blood”, “The Magnificent Eight”, “Pulp Fiction”, “The Pianist”, “The Book Thief”, “The Slumdog Millionaire”, “Freedom Writers”, “Great Debaters”, “In the Valley of Elah”, and “The Reader”.

How do you write? Does a story come to you, or a character comes first? What are the themes, issues, concern you address in your books?

Whether it is fiction, poetry, or articles, I always seek a spark. In literary writing, once I have the “revelation” or the spark of a certain story or a poem, it either pours itself onto the page or takes me ages to finish. I have written texts in a couple of hours. And at the same time, I still have a poem that I have been working on for more than 4 years. In fiction, I always feel that once I think of an event or an encounter or a bit of dialogue, the characters evolve accordingly and take the lead and free themselves from me as the writer.

If I am writing an article, the timing is important or else the topic loses its thunder. During Israel’s 2014 massacres, one of my articles had thousands of shares. It came soon after Israel bombed the Islamic University where I work and obliterated the offices of the Faculty of Arts. The article was entitled “There are no Poems of mass Destruction”. The article was timely, I brought my experience of teaching Jewish characters to Palestinian students in the piece. But I think the fact that the piece was cooking in my mind and heart for about 2 years helped it mature and reach out to greater audiences.

I classify what I write as resistance writing, as writing back, not that all I do is reacting to the political situations. In Palestine, everything has become political. Poetry is political. Fiction is political. Photography is political. Teaching is political. Living is political. But when I do write or when I teach my students to write, I urge them to transcend the particularities into the universal. I believe one reason “Gaza Writes Back” is a success is that it turned very personal Palestinian stories and voices into timeless and universal fiction that appeals to all regardless of age, race, ideology, ethnicity, or religion.

How important is language for you in your work?

Words. Words. Words. As Hamlet says. Language is all we have to voice our struggle and to fight back. The words are our most valuable treasure that we ought to utilise in order to educate ourselves and educate others. And these words ought to be conveyed in as many languages as possible. And no matter what, I believe in a language that touches the hearts and minds of as many people as possible.

How would you consider the Palestinian literary scene at the moment?

The Palestinian literary scene is, in my honest opinion, in disarray. The literary scene in Palestine has two major flaws: the chasm between the old and the young and the domination of non-Palestinian voices. Usually established writers who have done a great job for the Palestinian cause tend to look down upon emerging writers. Rarely do I see an event or a project where old and young people work together or where the established writers work with the young ones who really need the support and guidance of experienced writers. This gap has existed everywhere and it negatively influences the young writers. However, a silver lining here is that the young writers develop their own independent usually revolutionary identity that is more daring more unconventional.

Secondly, if you look at major pro-Palestine events, sometime they are dominated by pro-Palestinians voices. While they are significant and needed, these voices usually occupy the space that should be dedicated to Palestinian voices. In other words, while all sorts of support are welcome, it is Palestinians who have suffered 7 decades of occupation, terror, humiliation, dispossession, and injustices. Palestinians are more capable of conveying their message and concerns to the world. When Palestinian voices are muted or sidelined, we jeopardise the whole cause and doom Palestinian voices to oblivion. That is Palestinians should represent themselves; they should not be represented.

Therefore, more should be done to nurture emerging Palestinians voices, translate and showcase them, and present them to the world. The least to be done here is to constantly hold events for young Palestinians only, to publish their works, to fund their reading clubs and events, and to sponsor and encourage literary contests. These events can bring together Palestinians from Gaza, the West Bank, Jerusalem, areas occupied by Israel in 1948, and the Diaspora in one platform, where books and other forms of literary productions can be nurtured. This is how we can unify Palestine and create a Palestine that Israel and its allies are working very hard to prevent from existing.

What does literature mean to you?

Literature especially fiction is timeless and universal, and that is a fact. In my classes, we read fiction from all over the world across time and place and we still identify with the characters and feel sorry for their pains and happy for their gains regardless of their race, skin colour, ideology, or ethnicity. Reading literature and stories like the ones in Gaza Writes Back takes us to the homes, minds, and hearts of people from all over the world. Reading these stories helps people transcend the barriers of language, ideology and geography and brings us closer. A book like Gaza Writes Back is a reminder to people of all faiths that we are all human and that these little children exposed to the brutality of Israeli occupation could be us, could be our own children or nephews and nieces.

Still, literature has the ability to educate us, to heal us, to bring us all together, and to open up new possibilities of a better future. Literature has the ability to create bridges and reach out to all. That is why people who read and appreciate literature tend to be more thoughtful. And that is why totalitarian regimes hate literature. In the oppressed societies, literature is usually connected with their struggle and fight for human rights and justice. Literature becomes and is resistance. It is not strange then that Israel targets Palestinian intellectuals, novelists, and poets. Nowadays, Israel, for example is persecuting Palestinian poet Nadeen Tatour, whose only crime was to express herself in poetry. And it is reported that Israeli general Moshe Dayan likened reading Fadwa Tuqan’s poems to facing 20 commandos.

And connected to the previous question, we live in a world where the idea of “the other”, different from us is used to create fear of the other. How can literature help to defeat this fear? Break barriers and borders, walls?

Literature brings all together in one space, regardless of race, religion, skin colour, or ideology. Usually when we read literature we strip ourselves of our prejudice. Good writers usually help their readers identify with certain characters and bring us closer to their pain and plight. When start asking ourselves “what if we were in their shoes?”, truth about the fact that we are humans dawn on us and thus shatter prejudice.

A story about a small Palestinian kid’s last moments as he bleeds to death following an Israeli missile that targeted a group of kids playing football is usually an invitation to imagine ourselves or our loved ones in this situation. Good readers usually react responsibly, change their behaviours, attitudes, or even ideology. As Palestinians we’re counting on literature to break all barriers and walls built by the Israeli occupation and its misinformation campaigns to give voice to the voiceless and face to the faceless and take Palestine to the homes, lives, hearts, and minds of people all over the world.

Because literature liberates us from our prejudices and ideologies, it is an important tool of education and enlightenment. That is why we hope and have to work harder so that Palestinian literature reaches out to all, including Israeli occupiers. Who knows, maybe one day they will realise the absurdity and brutality of their occupation.

However, literature is a double-edged sword because it can also be used as a propaganda tool. This is true of much of Jewish literature in the end of the 19th century and the 20th century. For the Zionist movement, literature was used as a tool to convince the Jews of the world to go to Palestine. To do so, among many other unethical things, the Zionists presented Palestine as empty, as a land without a people, awaiting the so-called “rightful” people to go and enjoy its milk and honey. In much of Israeli literature, Palestinians are misrepresented and excluded. They do not have a voice or a face. And if they do, they’re mostly terrorists or backward.

Let’s talk about the initiative Gaza Writes Back. When did you start this, who is involved, what are the campaigns it runs?

The idea to compile a book of stories came to me during Israel’s 2008 attacks against Gaza that lasted 23 days. I spent these days telling my kids stories to distract them from the explosions and the gunpowder that was suffocating us. These stories sparked a passion for storytelling and took me back to my mother’s and grandmother’s stories. They made me realise I, as a person, am the sum of these stories. When I went back to my classes, I started assigning my students to write short fiction instead of research papers. I held several training courses in short story writing and creative writing. The result was amazing. I picked 23 stories from more than 100 pieces I collected. We wanted the 23 stories to counter Israel’s 23 days of terror.

Gaza Writes Back is first and foremost a book of literature, a book that came for the same reasons why all literature is written, and artistic activities are as old as human life. They signify willingness, usually daring, to resist the repetitiveness and dullness and dreariness of life. Literature defies all acts of suppression and oppression because oppressors are always dull and repetitive, while makers of art are creative and innovative. Literature stands out as a testimony for the generations to come. But literature is too a powerful means of self-expression and a sharp reflection on the world we live in, be it oppressive, repressive or even completely falling apart.

The short fiction pieces in Gaza Writes Back were compiled to become a testament of the importance of one’s determination to live and resist occupation and oppression for the future Palestinians just like we now read Ghassan Kanafani more than history books. Moreover, writing a book like Gaza Writes Back is part of our duty and moral obligation as young Palestinians to reach out to the whole world to educate them, and thus us, about our plight under the racist Zionist occupation.

Gaza Writes Back humanizes the Palestinian plight and universalizes it. It gives voice to the voiceless and a face and a name to the faceless at a time when the all-powerful Israeli narrative is distorting all facts and figures. And the book, I believe, generated more books and literature in Palestine.

More young Palestinian writers are now more willing to write and express themselves openly, because they have seen how a short story or a book can make a huge difference. Several young Palestinians have approached me and asked me for advice or feedback on their pieces. In my classes at the Islamic University, Gaza, I am witnessing a surge in the number of students who want to write, especially fiction. And I also know that many are now working to document the last war in the form of stories similar to those in Gaza Writes Back.