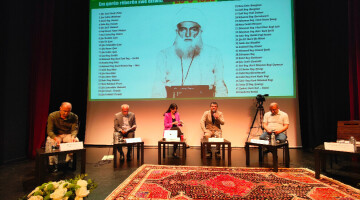

A two-day conference titled “The Sheikh Said Uprising, the Azadî Movement, Sheikh Said and companions, memory and collective opposition in its 100th year” was held at Centre Culturel Espace Magh in Brussels on Friday and Saturday. The conference was organized by the Kurdistan National Congress (KNK), the Kurdistan Islamic Community (CÎK), and the Kurdish Institutes in Germany and Belgium.

On the second day of the conference, discussions focused on the impacts of resistance on different parts of Kurdistan, migration and exile processes, and the social and political dynamics that developed after resistance.

Fourth session

The conference began on the second day with the fourth session, moderated by Kübra Sağır.

Researcher and writer Mehmet Bayrak, who made a presentation titled “Eastern Reform Plans and Their Reflections on the Present Day”, said the following: “New information and documents regarding the 1925 Kurdish uprising have come to light. These documents reveal that the state adopted a confessional, repressive, and denialist approach in its secret plans, contrary to its official discourse. Many truths that have been openly denied are acknowledged in secret documents, revealing the dual nature of state policies toward Kurds in Turkey. Despite being one of the ancient peoples in these lands, the Kurds have been subjected to oppression, deportation, and assimilation policies since the 19th century. Modern Kurdish organizations began with the Kurdish-Armenian Independence Committee in Dersim in 1865 and continued with the Kurdish Azmi Kavmi Society in 1901. By 1921, approximately 20 Kurdish democratic organizations had been established. These organizations focused on cultural and educational activities and political work. During this period, 15 Kurdish-language publications were issued.

The Union of Progress (tr: İttihat Terakki) cadres prepared false documents, fabricated books, and manipulative reports. Kurdish history, identity, and existence were denied through official and fabricated documents. In these documents, Kurds were defined as a “threat,” and measures to be taken against them included deportation, cultural eradication, and assimilation. During this period, an “ethno-religious cleansing” policy was implemented step by step. This became the policy of the new Turkish state. The Kemalist administration also implemented it. The state's goal was clear: to create a Turkic state. The reports that paved the way for this process were prepared primarily by Talat Pasha and his associates. In this context, he assigned Ziya Gökalp for the preparation of fabricated books that distorted the history of the Kurds and belittled them, and fabricated studies claiming that the Kurds had no origins. The aim was to deny the Kurdish identity and erase their history. These fabricated information and slanders turned into actual politics during the Kemalist regime and became a state policy. The deportation and displacement of the Kurdish population, their exclusion from education, and the banning of their language were systematically implemented. The issue of autonomy for Kurdistan was intensely debated in Parliament during a session on February 10, 1921, and a bill granting autonomy to Kurdistan was submitted to the Assembly. However, when we look at the Assembly minutes today, the records from that period have been erased, as if nothing had ever been discussed. In reality, secret negotiations took place between the Kemalist administration and some Kurdish representatives.”

Assoc. Prof. Dr. İbrahim Malazada gave a presentation on “The political and social impact of the Sheikh Said Uprising in South Kurdistan.” Malazada emphasized that although the Sheikh Said uprising did not directly spark a major reaction in South Kurdistan, it had a powerful influence in political, social, and spiritual terms. He stated that Sheikh Said's affiliation with the Naqshbandi Order and his status as a spiritual leader deeply influenced society in South Kurdistan due to the strong influence of this order in the region. Malazada stated that the uprising was based on the protection of Kurdish identity and freedom and the establishment of Kurdistan: "We know that the southern borders were closed during the uprising. Communication conditions were not like they are today. Therefore, there was no direct participation from the South, and even if there had been a possibility, the early suppression of the uprising would have played a role. However, after the uprising, many Kurdish leaders came to Southern Kurdistan. The experience and political knowledge they gained here had a significant impact in the South. It also played a role in shaping Kurdish politics here."

Dr. Azad Haj Aghay gave a presentation titled “Rojhilat Kurdistan, Kurdish Movement Between Past and Future: The Sheikh Said Uprising.” Aghay spoke about the development of Kurdish political and cultural movements centered in Istanbul in the 1900s and touched on the impact of this process on Rojhilat (Eastern Kurdistan). He noted that many Kurdish intellectuals and politicians from Rojhilat came to Istanbul during that period and established contacts with Kurdish organizations and publications: “These contacts made significant contributions to the development of the Kurdish political movement. In particular, the work and written publications centered in Istanbul and Southern Kurdistan, along with political aspirations, both transformed Rojhilat Kurdistan and contributed to the formation of its politics."

Aghay stated that the center of Kurdish politics in the 1900s was Bakur (Northern Kurdistan), and cited examples of how Kurdish politics centered in Istanbul influenced Rojhilat. Aghay noted that there is limited documentary evidence directly linking the Sheikh Said uprising to Rojhilat, but mentioned that a newspaper published in Russia at the time reported that Kurds living in Iran's Azerbaijan region were preparing to join the uprising. Aghay stated that the politicians and resistance fighters who were exiled from Bakur to Rojhilat after the uprising also had an influence on the establishment of the Mahabad Kurdish Republic, and that Sheikh Said was highly praised and embraced in a magazine published during the Mahabad Republic era.

Giving a presentation on “The Impact of the 1925 Uprising on the Kurds in Rojava and Syria”, lawyer and writer Şoreş Derweş said: "Especially during the French period, the population of Cizirê and its surroundings was predominantly Kurdish. The idea of establishing a state also developed at that time. Exiled politicians who had fled to Syria after the Sheikh Said Uprising played a major role in these efforts. However, the Turkish state's relations with France developed entirely around the Rojava region. The policy of preventing Kurds from becoming the majority in the cities there was implemented by the French at the request of the Turkish state. The Kurdish population was deliberately kept in villages and small towns. This is particularly evident in Hesekê. The borders with the Turkish state were drawn in 1921, but were finalized in 1923 and 1925. Here, we observe that the Turkish state's hostility toward the Kurds was based on French interests, which also intervened in Kurdish affairs. During this period, special policies were implemented against the Kurds. The impact of the Sheikh Said uprising was significant in Rojava and continues to this day. Political debates and the formation of parties during that period were shaped by this legacy. The influence of those debates can still be felt in many parties today.”

Fifth session

The conference concluded with the fifth session, where the cultural, social, and literary dimensions of the Sheikh Said uprising were discussed from different perspectives. The conference ended with a comprehensive examination of the place of this historical event in social memory in the context of migration, exile, state violence, oral culture, and literature.

Moderated by Dr. Ayhan Işık, the fifth session discussed “Sheikh Said and the Freedom Movement's Place in Cultural, Literary, and Social Memory.”

Doctoral candidate Merve Fırat gave a presentation titled “Forced Migration and Exile Policies Following the 1925 Sheikh Said Movement.” Fırat discussed the exile experienced by the Sheikh Said family in particular and the exiles that took place in Kurdistan following the uprising. She highlighted the tragic events and resistance practices during this migration process, and continued her presentation by referencing historical documents to explain the political activities centered in Iran and Iraq that were behind the problems encountered in Iran.

Fırat said that Sheikh Alirıza's efforts to achieve political unity among Kurds in Iran and Iraq were blocked by British policies at the time and that he was forced to live in Baghdad. Fırat described the exile and forced residence policies that followed the uprising, citing examples of families, and presented documents detailing the tragedies and struggles of women and children exiled to the West who did not know Turkish.

Drawing attention to the fact that the Sheikh Said family and many segments from Kurdistan experienced two separate periods of exile and forced residence after the uprising, she explained the hardships these families endured throughout history and the struggle they waged to preserve Kurdish culture while in forced residence.

Dr. Delal Aydın addressed the topic “From Sheikh Said to the Present: The Continuity of State Violence and Kurdish Resistance." Aydın stated that the 1925 uprising was not merely an uprising, pointing out that it was a critical period in which the republican regime sought to eliminate uncertainties and reestablish its authority. During this process, she said, the state sought to suppress Kurdish identity not only physically, but also symbolically and socially. Defining the events that followed the uprising as a period of constant repression and a continuation of the policy of violence against the people, Aydın said, “What happened in 1925 was also part of that period.” Aydın emphasized that Sheikh Said was both a religious and national leader and a symbol, and that his execution was also an intervention targeting the memory, identity, and future of the Kurdish people.

Lawyer and writer Ömer Güneş, in his presentation titled “The Influence of Dengbej Art and Kurdish Music at the Heart of the 1925 Freedom Movement,” emphasized the central role that dengbej art played in the Sheikh Said uprising and the social memory of that period.

Güneş stated that the oral narratives of dengbej singers preserve both collective memory and individual experiences by passing down historical events and personal tragedies from generation to generation, adding, “This oral art form contributes to the preservation of historical consciousness by being shared in social spaces where people gather, such as coffee houses, in the homes of prominent members of society, and at various community gatherings.”

Güneş said that the dengbej art did not only develop as an art form, but also as a cultural memory tool that kept alive a spirit of resistance and identity.

Assoc. Prof. Selim Temo gave a presentation on “Sheikh Said in Kurdish literature and poetry,” discussing the movement and its reflections on poetry and literature during and after that period.

He explained the meanings of the Sheikh Said uprising and the historical figures that followed in literary texts, citing examples to illustrate the continuity between the metaphorical language of poetry and historical reality.