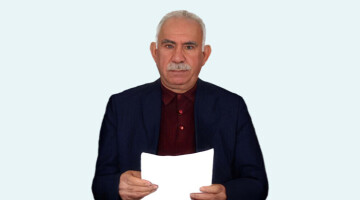

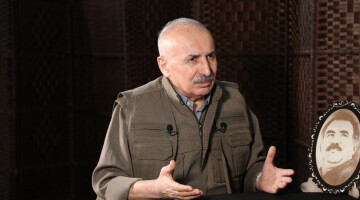

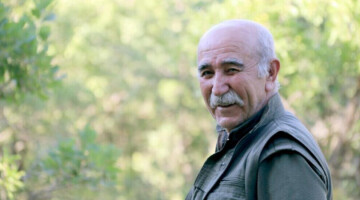

Yusuf Demirci has spent his life as a shepherd between the restricted villages on Mount Gabar in the Northern Kurdistan province of Şırnak. Hidden like a smuggler, his father and his wife Nafise Demirci and their ten children move through the restricted areas. He describes his profession as saying: "We are a kind of guardian of these mountains."

The fifty-year-old tells that he has been a shepherd for as long as he can remember and continues: "I have 500 animals. But I also take at least 200 sheep from the villagers. With my wife and ten children, I spend most of the year in the mountains. One cannot say that we are nomads or that we are sedentary. But one can call us the guardian of Cudi and Gabar for 50 years."

The village in which they live is called Cınnet: "This village was completely burned down and evacuated 50 years ago. Previously, Syriac people used to live in the village. But at that time they were either killed or moved to Europe. There are almost no villages left here on Gabar. One after the other was burned down and the population was expelled. Only those who wanted to serve as village guards [paramilitaries loyal to the state] remained. Proud Kurds who did not accept this had to flee like the people from Cınnetlı."

"We did not take the arms of the state"

"We did not sell our honor. We did not take the state’s arms," says Demirci, reporting that he is from the village of Dara, near the province of Şırnak. Sometimes he comes here for money, sometimes secretly, to feed his animals. "There is one man who is called the Ismail of Abdulaziz. He has issued this village as his own and obtained a corresponding title from the state. Sometimes I get his permission. In return, I take his sheep to the pasture without charge. In some years, if he does not want me to feed his animals, then we agree that I give him seven sheep."

Summers are light and winters are heavy, tells Demirci, concluding with the words: "The price of animal feed breaks our backbones. The state exerts double pressure so that we do not graze our animals. We used to be free. My animals were also free, like the land and me. To come here secretly is hard. Traveling with so many animals also limits the range of motion. In a few years, scores of my animals were killed by the state and I was barely able to save myself. Today, the same danger still exists, but I cannot do any other work. This job will cost me my life. My kids will do the same."