Kobanê witnessed one of the greatest resistances in history. It was liberated on 26 January2015, and 1 November, the date the resistance began, was declared World Kobanê Day.

This resistance also became a source of hope and inspiration for many internationalists fighting for humanity, and many set off for Rojava. One of them was British Hêlîn Qereçox (Anna Campbell).

Hêlîn Qereçox fell as a martyr as a result of an airstrike by the Turkish state during the Afrin resistance on 15 March 2018.

The young British woman set out from Britain to Rojava with revolutionary enthusiasm and determination.

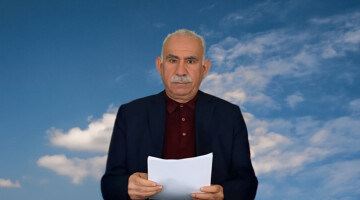

Anna Campbell's father, Dirk Campbell, spoke to Yeni Özgür Politika about his daughter, her belief in the Rojava Revolution, and how she was affected by the Kurdish people's struggle for freedom and resistance.

Could you share with us some moments from Anna’s childhood and youth?

Anna was born six weeks premature and spent her first two weeks of life in an incubator, being fed her mother’s breast milk down a tube. This experience was highly traumatic for her mother and she always had concern about Anna’s fragility. Anna may not have been physically strong, but she had a strong will and a strong sense of her own identity. She loved fairy tales and learned to read early. She enjoyed being the leader of her two younger siblings and creating complex fantasy worlds for them to inhabit. She had deep feeiings, and would express strong grief at the loss of a toy or a pet. She did not like the ordinary school environment because of its insensitivity, and as a young child had physical pains because of this, so we home-educated her. Her mother started a child-centred school in Lewes, the town we eventually moved to, where Anna was happy. A number of children with special needs attended this school and Anna gave them her time and attention when no-one else would. When she was too old for her mother’s school, we paid for her to be educated at a private girls’ school; as before, she could not cope with the culture at state schools.

After leaving school, Anna spent a year as an au pair in Paris, where she was able to indulge her love of literature, and also attended festivals. She was discovering her sexuality and realised she was gay. She then went to Sheffield University where her friendship group was on the political far left, and it is from this, combined with her passion for justice, that all her affinities and activities derived, such as Dale Farm, the Calais Jungle, Le Zad, Hambacher Forest, anti-fascist demonstrations, environmental activism and hunt sabotage.

Did you or any of her close ones have an influence on Anna becoming an international revolutionary? For example, did the environment and atmosphere she grew up in play a role in her sympathy towards a revolutionary struggle?

No, her mother and I didn’t know anything about the revolutionary struggle. We talked about the natural environment, climate change, peak oil and that kind of thing.

Can you tell us about Anna’s journey to Rojava? Did she share her initial decision to go with you? Did she consult you before making this decision? If she did share it with you, what kind of conversation did you have? Did you oppose her decision to go to Rojava? Could you describe this process for us?

She told me she had decided to go to Rojava. She didn’t consult me beforehand. I knew she was putting herself in danger, but since I knew this was now habitual for her, and that once she had decided on something it was impossible to argue her out of it, I didn’t try. She thought she knew what she was doing. I merely said ‘It’s been nice knowing you.’ Her mother had died in 2012 of metastasized breast cancer, so she was not there to argue her out of it, which she would have done her best to do. In fact, if her mother had been alive, Anna would not have died in Rojava, firstly because she would not have felt she had to take on her mother’s pioneering role, and secondly, because her mother would have gone to great lengths to prevent her from going to Rojava and, and if she had succeeded in going, to bring her back.

While Anna was in Rojava, were you in communication with her? What did Anna share with you while she was there? How did she feel in Rojava? What impacted her the most? Could you tell us about it?

Anna felt very much at home with the Rojava people and the YPJ. She loved the fighters, they were soul mates for her, and she wanted to be like them. She had initially only gone for a year, but it became obvious to us that she was unlikely to come back. She felt Rojava was her purpose in life. I didn’t get to speak to her much because of difficulty with phone technology, but she spoke more to her siblings, and they got this impression. Öcalan’s political ideology combined with womens’ studies (jineoloji) made a great impression on her. Feeling that she could fight as a revolutionary for a cause which she was passionate about, for good, solid ethical reasons, made her happy and satisfied.

What was your last conversation with Anna like? Did you know she was going to Afrin?

My last conversation was in January 2017. She said the commanders wouldn’t let her go to Afrin, which was a relief to me. In fact, she lied, she had finally got permission to go, so none of us knew.

We know that Anna’s remains are in Afrin, controlled by militias. You are fighting to retrieve her body. Why haven’t her remains been handed over to you? Have you been able to visit the cemetery in Afrin? Could you tell us the current situation?

Her remains haven’t been handed over to you, and you’ve taken this matter to the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR).

Anna’s remains have not been recovered. The Kurds were not able to recover the remains of any of their dead as they were being fired on by the Turks. There will be nothing left of her body by now. I took legal action in 2019 on the advice of McCue and Partners, now McCue Jury and Partners, that a crowd-funded legal action could get redress from the Turkish government for their breach of my human right in not returning her remains, which they are obliged to do under the Geneva Convention and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, both of which they are signatories to. The crowd fund raised £25,000.

McCues had to prepare a case to present to the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC). This took a lot of time and effort. I said to McCues not to bother with the ICRC as I had appealed to them initially, they had said they would contact the Red Crescent in Turkey as they were not themselves able to enter a war zone. They never contacted me or responded to my requests for information, so nothing had happened for eighteen months. The same was true of the British Foreign Office, I had two meetings with the Minister for the Middle East, Alastair Burt, who promised to represent my case to the Turks but did nothing.

McCues said that the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) would require contact with the ICRC as part of due process. As I predicted, the ICRC did nothing but prevaricate and delay and talk about the importance of protecting their reputation. We got nothing from them.

The next step was to appoint Turkish legal counsel and put my case to the Hatay adminstration responsible for Turkish-controlled Afrin. Turkish counsel did this and received no response from the Hatay administration. After the response date had expired, McCues took my case to the ECHR on the basis that due process had been observed. While the ECHR was considering the case, the Hatay administration responded to Turkish counsel, which meant that the ECHR had to dismiss the case on the basis that we were now able to get my case considered by Hatay. This happened in June this year.

So, six and a half years after Anna’s death, I am not much further forward. A second crowd fund was organised which raised £19,000, about £6,000 of which is left and is paying for Turkish counsel’s costs. They say it will probably take three years for my case to go through the Hatay court system.

Could you explain why you took this step?

In order to try to shed some light on the Turks’ war crimes, atrocities and human rights abuses. Although even if the ECHR finds in my favour there will not be much of an outcome from that, because all they can do is reprimand the Turks for breaching my human rights, tell them not to do it again and order them to provide reparations, which they are highly unlikely to do. The Turks know they are in a very strong position politically and economically vis-a-vis the European Union, so that their human rights record will probably be overlooked in their dealings with the EU.

If you are able to retrieve Anna’s body, will you bring her back to England, or will you bury her in Rojava, where you say her people are?

I won’t be able to retrieve it as there are no remains to retrieve.

What message would you like to send to the Kurdish people and the internationalist revolutionary forces resisting in Rojava?

I am sorry to say I have very little to offer the Rojava Kurds in terms of hope or support. I applaud their efforts, of course, and I am full of admiration for them, particularly their dignity and refusal to accept defeat when they are surrounded by enemies and antagonists on all sides. All I can say to them - to you - is that I know you will fight for justice and true humanity to the end, as Anna did, and as all your martyrs have done. I do talk and give presentations on Rojava and Öcalan’s ideas whenever I have the opportunity.