When it comes to social ecology, the first name that comes to mind is Murray Bookchin. The renowned American thinker and theorist passed away in 2006, but his ideas remain influential to this day. With his theory of social ecology, Bookchin argued that ecological problems are not just caused by environmental factors but also have social roots. In his view, a sustainable and ecologically balanced society could only emerge if hierarchical and oppressive structures were abolished and replaced by a social system based on direct democracy.

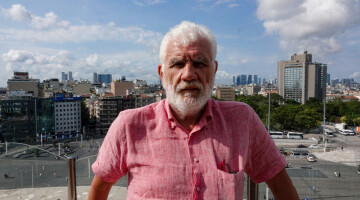

Janet Biehl, a researcher, author, and artist who was Bookchin’s companion for the last 19 years of his life and wrote books and articles about social ecology and the Rojava revolution, spoke with ANF about the brief but remarkable correspondence Bookchin and Abdullah Öcalan had.

You were one of the people who closely witnessed the letter exchange between Murray Bookchin and Abdullah Öcalan. Could you tell us a bit about this process?

I was Murray Bookchin’s life and work partner for the last 19 years of his life. We lived in Burlington, Vermont. When I met him, he was a well-known social theorist advocating for direct democracy through grassroots citizen assemblies. He was a radical throughout his life and spent his entire adult years trying to build a movement around this idea. However, this process was quite exhausting and filled with disappointments. Despite all the challenges, he gained significant supporters, and his books were translated into different languages.

In the mid-1990s, a publishing house in Istanbul approached him with an offer to translate some of his books into Turkish. He signed the contract. I remember the moment I put the contract in an envelope, stamped it, and dropped it in the mailbox. I thought to myself: Turkey? Social Ecology? Impossible. But I sent it anyway. Later, it turned out to be the most important agreement he had ever signed. His books were translated into Turkish, and, along with many other social theory works, they were sent to Mr. Öcalan on Imrali Island after he was arrested and sentenced to life in prison in 1999.

Mr. Öcalan read those books. Everyone said he was very influenced by them.

There is one thing I personally witnessed. In April 2004, we received an email in our inbox. The message came from a comrade in Germany, a Kurdish activist from the Öcalan Freedom Movement. He was writing to Murray, saying, “Mr. Öcalan has read your books and is very interested in your ideas. Is it possible for us to establish a dialogue or conversation?”

By this time, Murray was not so well. He only had two years left to live. He experienced many disappointments throughout his life. You know how frustrating that can be. He didn’t know much about what was happening in Kurdistan. He thought Öcalan was just a former Marxist. When he received the message, he responded, “Oh, that’s nice. I’m happy to hear he is interested in my ideas. Look, here’s a list of some of my books that have been translated into Turkish.”

This message wasn’t sent directly to Öcalan but first to the German intermediary, who then passed it on to Öcalan’s lawyers, and finally, the list reached Öcalan.

There were a few more letter exchanges after that. If I’m not mistaken, there were some theoretical discussions, even if not very deep. Correct?

Yes. Very shortly after, we received another message through the same communication channel. In this message, Mr. Öcalan said: “I am a good student of your ideas. I see myself as a social ecologist.” Social ecology was the name Murray gave for his own ideas. What Öcalan embraced most clearly was the ecological approach and its connection to grassroots democracy. In other words, the idea that people should make decisions about their own communities instead of being exploited by large corporations and big governments.

This actually made perfect sense. The Kurds, the world’s largest stateless ethnic group, live as minorities in different countries and naturally sought a non-state-based solution.

Murray first identified as an anarchist, then as a communalist, but he was always anti-state. His ideas revolved around a stateless society and a stateless democracy. So, it’s not difficult to understand why these ideas appealed to Mr. Abdullah Öcalan.

During this time, Murray’s health was deteriorating. He was very weak and suffering from various problems. He responded to Öcalan with the following words: “Mr. Öcalan, I am not in a position to engage in a dialogue with you. But I am truly happy to hear that the Kurdish Movement is in the hands of a capable leader like you. I hope you can bring these ideas to life.”

It seems this response was well-received, and as far as I understand, Öcalan proposed transforming these ideas into democratic confederalism. He presented these ideas to the PKK, and they accepted them. In a short time, it became the PKK’s paradigm.

When Murray Bookchin passed away, the PKK sent a condolence message. How did that message affect you?

Yes, when we lost Murray, the most beautiful condolence message came from the PKK. They wrote: “We salute Bookchin, the great social theorist of the 20th century who taught us the path of ecology and democracy. We promise to build the first society based on his ideas.”

This was truly extraordinary, and I wish Murray could have seen it. Honestly, I didn’t know how to react to this message. I wrote back to them and said, “This is very beautiful.” At that time, and even today, the PKK was on the U.S. State Department’s list of ‘foreign terrorist organizations.’ I didn’t know what this meant for me. If I maintained good relations with them, would I be thrown into federal prison? I really didn’t know what to do. So, after thanking them, I actually focused on another project: writing Murray Bookchin’s biography. I interviewed many people who knew him in his youth and spent more than five years researching and organizing materials for his biography.

In 2011, you attended a conference in Amed as a speaker. If I’m not mistaken, this was the first time you witnessed how deeply Bookchin’s ideas had taken root within the Kurdish Movement. Is that right?

Ercan Ayboğa, the founder of the Mesopotamian Ecology Movement, contacted me in 2011 and invited me to speak at a conference in Diyarbakır. I set aside my hesitations and decided to attend the conference. Seeing the ideas and excitement there was incredibly inspiring. There were women speaking out against honor killings, female lawyers, and human rights activists. I also met many human rights lawyers interested in these issues for the first time there.

There were discussions on ecology, nuclear energy, water resources, deforestation, capitalism, cooperation, and democracy. I particularly remember a young woman who approached me and started talking about Murray’s ideas. She had studied his ideas so well that she could explain them more clearly than I could. She spoke so beautifully and impressively that I was amazed.

You visited Rojava several times and even wrote a book, Journey to Rojava, based on your observations. When did you first go, and what impressed you the most during your visits?

I first went to Rojava in 2014. I later visited again in 2015 and 2019. One of the advantages of my second and third visits, spread over this time frame, was that I could observe the early days of the revolution and then return five years later to see what had changed. I can speak about that, but I can't say much about what is happening there now since I haven't had the chance to go in recent years.

One of the things I noticed during my early visits was the strong emphasis on inclusivity and the assurances that there would be no retaliation against the Arab communities in Rojava. Breaking the cycle of revenge was extremely important. In every academy I visited—including security, economic, and military academies—the fundamental lesson was always the same: No revenge.

For years, the regime had spread the idea among Arabs that "If one day the Kurds come to power, they will treat us the way we treated them." But my impressions and observations did not reflect that at all. There was a tremendous effort to avoid revenge, to avoid settling scores, and to establish the idea that the fates of Arabs and Kurds were intertwined. This principle was actively put into practice, creating a shared life among Kurds, Arabs, Chechens, Assyrians, Syriacs, and all the peoples of the region. Despite these efforts, there was still some tension in 2015.

When I returned in 2019, I realized that this was no longer a major issue. Why? The biggest reason was the war against ISIS. Even in conversations, I could see that the war had brought people together. By then, they had war experience. Arabs knew they could trust the Kurds. Kurds knew they could trust the Arabs. Women knew they could trust men. They had transformed into a unified fighting force that worked in harmony. It was truly impressive.

While in Kobanê, I attended a neighborhood assembly meeting and asked about this issue. A man answered, "Our blood has mixed." In other words, he was saying that in the fight against ISIS, they had become one people. That response was deeply moving.

Many academics have written articles highlighting how Murray Bookchin’s ideas merged with Öcalan’s and became a reality in Rojava. What were your impressions?

If a model inspires you, it is important to consider how you can implement it in your own country while taking reality into account. You can’t recreate conditions everywhere. The situation in Rojava was unique. The Assad regime was forced to withdraw from the north of the country. The Kurdish Movement filled the power vacuum. Such an opportunity rarely arises in history.

What impressed me most about the Kurdish Movement was that when this moment came, they were ready. They had educated themselves. They studied the theory and adapted it to their needs. They understood that this was the way forward.

I personally would love to live in a society governed by stateless democracy. I think it’s crucial to explore how we can implement these ideas in our own societies. Even if it’s not possible now, we must be ready when historical conditions change. You never know when that moment will come.

The world is currently in turmoil. Authoritarian forces are trying to reshape societies on the model of leaders like Erdoğan and solidify dictatorships. Meanwhile, there are societies advocating for different types of democracy—some for representative democracy, some for constitutional republics, and some, like Rojava, for grassroots direct democracy. Until authoritarian forces are defeated, I believe we must all unite to defend democracy in whatever form it takes. That should be our priority.

You emphasized the importance of the Rojava Revolution for the future of democracy. What needs to be done to protect this model?

I believe that everyone who cares about Rojava should write to their governments. This movement may be anti-statist or stateless, but governments have a significant impact on geopolitics, and they are the ones we need to engage with. I live in the United States, and I regularly write to my senators and members of Congress about Rojava. I tell them that the U.S. must not abandon our Kurdish allies, who fought alongside us against ISIS. I remind them that the Kurds lost 11,000 people in that war and that we must stand by them. Everyone should do the same in their own country.