Halil Dağ - a guerrilla, filmmaker, journalist

This our own way, our attitude and our view of life is something we no longer give away after all we have experienced…

This our own way, our attitude and our view of life is something we no longer give away after all we have experienced…

Today marks the twelfth anniversary of the death of Halil Uysal – the “guiding star of Kurdish cinema”. In 2007, Kurdish guerrilla fighter, writer and filmmaker Halil Uysal travelled from Southern Kurdistan (Başûr) to Mount Ararat to shoot a documentary. He only made it as far as Besta, where he was killed in action against the Turkish army on April 1, 2008.

Uysal, called Halil Dağ by the guerrillas, was born in Germany in 1973 as the son of a Turkish father and Kurdish mother. When he finished primary school, the family went back to Turkey. After graduating from a private school in the western Turkish metropolis of Izmir, Uysal returned to Germany in the early 1990s. During the day he went to work, in the evening he attended photography courses. At some point he became acquainted with the Kurdish freedom movement. When MED TV, the first Kurdish television station, went on air in 1994, he was already considered one of the co-founders. There, he also gained his first experiences as a cameraman.

During his stay in Syria’s capital Damascus, he planned as a short visit for filming at the PKK party school in 1995, he was so impressed by the Kurdish liberation struggle that he decided to stay there and join the guerrillas. He himself wrote about this time: “On April 1, 1995, I traveled to the Middle East as an assistant to a German cameraman for an interview with Abdullah Ocalan. I got to know the guerrilla fighters in the central party school of the PKK better during the interview. After this interview with Abdullah Ocalan, which is also my first meaningful work, I decided not to return and to continue my life’s journey here. Since then, my life has been unfolding in the mountains of Kurdistan, together with the Kurdish freedom fighters.”

Departure from Syria, trip to Southern Kurdistan

In the beginning Uysal worked as a photographer with his very limited training. But the more time passed, the more passionate he became, reflecting on the world around him with his sharp powers of observation and a keen sense for the harmony betweenthe guerrilla and nature. He also became an active member of the free Kurdish press and reported about the war for various news agencies. In 1997, for example, he filmed the shooting down of a Turkish military helicopter by a guerrilla anti-aircraft missile – the scene was the media highlight of the PKK’s year of struggle at the time and generated a broad echo around the globe.

Undated photo of a sporadic hospital for wounded guerrilla fighters in the mountains of Southern Kurdistan © H. Uysal

Undated photo of a sporadic hospital for wounded guerrilla fighters in the mountains of Southern Kurdistan © H. Uysal

When Abdullah Öcalan had to leave Syria in October 1998 under pressure from Turkey after which he was abducted from Kenya to Turkey four months later after an odyssey through various European countries, the Kurdish movement also had to adapt to the new circumstances. Shortly after the PKK moved its headquarters to the Qendîl Mountains in southern Kurdistan, the Academy of Art and Culture Dibistana Şehîd Sefkan was founded. Halil Uysal was there from the first moment.

Sensational discovery

A short time later, he began to shoot his first short films. In 2006 he made the 150-minute film “Bêrîtan”, which was received enthusiastically by the Kurdish population. “Bêrîtan” tells the story of the legendary guerrilla commander Gülnaz Karataş, who survived 25 days in the battle zone in 1992 until her spectacular death made her unforgettable among friend and enemy. She had thrown herself off a rock to escape capture by peshmerga forces of the KDP (Kurdistan Democratic Party), which collaborated with the Turkish army. During filming on original locations, the previously unknown grave of Bêrîtan was discovered. The exhumation and transfer of her remains to a new grave frames the film’s plot and gives “Bêrîtan” an even more authentic character. The film, whose many battle scenes were shot with live ammunition and real grenades, with the protagonists being real guerrilla fighters, can technically easily keep up with far more elaborate productions – an amazing achievement by the film team. Bêrîtan was also shown in several European cities as part of film festivals.

“All the films from the mountains are now orphans”

Halil Uysal also had a passion for writing. He wrote particularly about the life of the guerrillas. His first memoirs were published in 2000 by the Mesopotamian publishing house under the name “Halilin Gözü” (Halil’s eye). In 2008 his book “Beni Bağışlayın: Dağ Yazıları & Botan Günlüğü” (Forgive me: writings from the mountains & diary from Botan). Both titles are currently not available, as the Neuss publishing house was banned by a decree of the German Federal Ministry of Interior in early 2019.

For his last project “The Travellers to Mount Ararat” he stayed in Northern Kurdistan from 2007. He wanted to accompany a guerrilla unit up to Ararat with his camera. Unfortunately he only made it as far as the region of Botan. Already on his journey there, Uysal got into a fight with the Turkish army and was injured on his right arm. His comrades gave him fire cover so that he could survive. But some time later, during an extensive military operation from 28 March to 1 April 2008 in Besta in the province Şirnex (Turkish: Şırnak), he lost his life in an ambush together with three other guerrilla fighters – İrfan Akkuş, (Masiro Gortun), Evin Bingül (Ararat Adar) and Beyan Alim (Doza Welat).

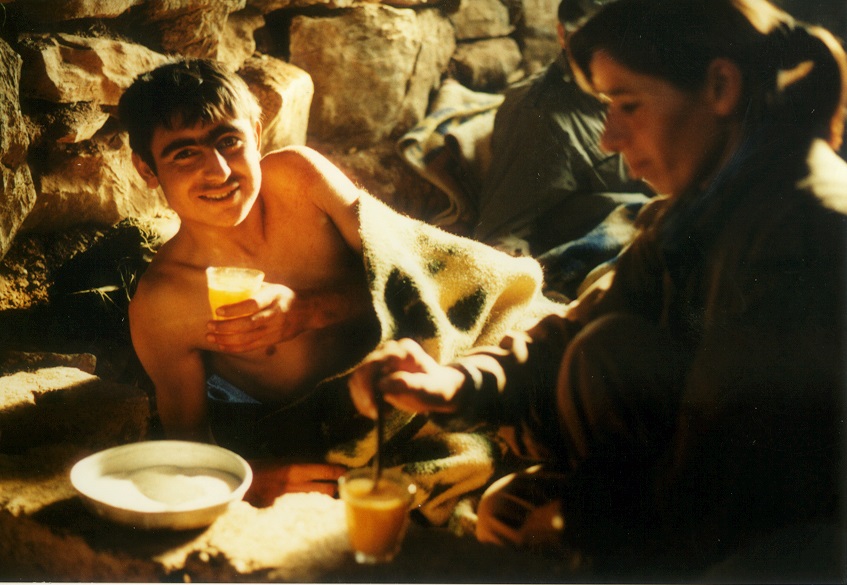

Kurdish guerrilla fighters © H. Uysal

Kurdish guerrilla fighters © H. Uysal

The death of Halil Uysal upset not only those who knew him personally, but all those who had seen his films or read his articles. He knew how to create closeness between himself and his readers in his texts.

In memory of him we publish two of his texts. “I will save you…” is the first text of his Botan Journey series. The second text is from “My heart beats for the mountains – Selected texts by Halil Uysal”. The book, translated into German by Meral Çiçek, was already in print, but could not be published due to a publishing ban.

“I will save you…”

I’ve called for him several times: Cûdi, get up… get up, let’s go from here. Look, this is the last (military) position. Look, this is the last cauldron… The friends are right over there… get up, I beg you, get up…

I quickly took my backpack, in which I carried my camera – which I guard like my own eyeballs – from my shoulder in pain. It was the same bullet that pierced my arm and my bag.

All I could do was take a quick look at my bag and at my loyal friend – my camera. I owed it my loyalty. Thanks to it I got to know the Kurdish freedom movement. My journey from Europe to the Middle East started with it. Together we had taken the first step into the mountains and got to know the guerrillas. Every work that I started with it, I finished with success. Nothing was left half done. It was the friend who made me who I am today. But the moment of separation had come.

When the hand grenade fell beside us, all I could do was wrap the tapes around my neck and throw myself aside. Underneath the explosion and the hail of bullets I looked back at my camera once more.

When Cûdî pointed to the opposite position and shouted that we should attack it, my thoughts went through my head to the memories on my neck and arm. When I set off, I got them from my friends for good luck: the girl’s watch on my arm, the leather strap – without reminding me exactly where it came from -, a piece Şutîk (a long scarf tied around my waist by the guerrillas) that I had taken from Bêrîtan’s grave, the muska (an amulet with a written meaning) around my neck, for which I gave my word to wear it for five hundred years, and all the faces of my friends who gave me these objects appeared before my eyes.

Would all these keepsakes really protect me or are they just a story?

Winter in Kurdistan, date of recording unknown © H. Uysal

Winter in Kurdistan, date of recording unknown © H. Uysal

This went through my mind as I took the muska between my teeth and moved together with Cûdî towards the opposite position. While I was waiting for one of the hundreds of bullets fired to pierce my body, I noticed that I was walking over soldiers’ graves. Everything happened in an instant and the opposite position had fallen.

My eyes were looking for Cûdî. Under the roar of the guns I cried out with full force: “CûdÎÎÎÎÎ!” But there was no answer. While I reloaded my magazine to return the shots from the side position, I kept screaming. But I could not hear Cûdî’s voice.

Then I saw Cûdî. He was leaning against a rock, his chest stretched out, standing in all his serenity. He stopped shooting. The enemy bullets came one after the other and pierced his blood-drenched chest. There was no expression of pain in his beautiful face. I called out to him several times: “Get up Cûdî … Get up, let’s go from here. Look, this is the last position… Look, this is the last encirclement… Get up… I beg you, get up… Don’t leave me alone in this encirclement… Get up, Cûdî, get up…

I can’t remember how many times I called his name. I don’t know how long I was in that hail of bullets. Time flew by like a lifetime, and Cûdî never left his place. With his unique wet eyes he looked at me for the last time, only I could hear his following words under the noise of the guns: “I told you, you will come out from under my cover of fire…”

That night, when the helicopter dropped soldiers on Mount Pervari to search for survivors, I marched lonely, my injured right arm and heart aching from the blowing of the cold wind. In this darkness, the words of Cûdî stuck between my trembling lips and tears flowed from my eyes that nobody could see.

This young guerrilla had kept his word, and I…

Murat Karayilan (3rd from left), on the right Celal Başkale (Mahir Koç), killed in April 2012 in Amasya © H. Uysal

Murat Karayilan (3rd from left), on the right Celal Başkale (Mahir Koç), killed in April 2012 in Amasya © H. Uysal

The Path

The path is the place where we begin to get to know ourselves and our counterpart. For this we only need to have made the decision once to set out and take the first step. We only have to have the courage to look at the path once. We must have dreamed only once of leaving the place of which we are prisoners. Just once the euphoria of finding something new, of discovering something new, must fill our inner being. Just once we have to make the decision to search for ourselves and set off…

Then the path will spread out before us with all its goodness. The path is always open to everyone. It may even be the only place on earth that awaits us all with open arms and leads human beings to themselves.

Is there anything more beautiful than self-discovery? Is the human being itself not the most beautiful gemstone on earth? And is not the most beautiful journey of our life the journey to ourselves? So far we have not really moved forward at all. The paths we have taken in the concrete cities, which always lead back to the beginning, are not ours. Not one of these paths has led us to ourselves. We have always looked at these cities, which do not belong to us, from a distance. We have always been strangers. If we stand in the evening at the same door from which we stepped in the morning, it means that we have not made any progress.

The first thing a guerrilla new to the mountains experiences is the pain of running. Every single step drives unbearable pain into our whole body. We then wonder why our feet are so powerless. Only then do we realize that the concrete roads have deceived us.

In our first days in the mountains our feet, shoulders and arms get to know an unbearable pain. With every step we take, our whole body writhes in pain. We then believe that we will never get rid of this pain. We turn our eyes to the mountain ranges ahead of us and almost lose hope. On these paths, all the loads that do not belong to us evaporate. Step by step our masks fall off and stay behind on the paths we walk. Step by step we leave behind on the slopes of the mountains the life that has been imposed on us for thousands of years.

Guerrilla fighter marching in the snow © H. Uysal

Guerrilla fighter marching in the snow © H. Uysal

While we can march on the paths of the mountains, we feel our body leaving us limb by limb. We feel the shell that holds body and soul crumble. This pain is unbearable. We feel ourselves distancing. We feel that we are leaving something behind. That is our dissolution.

We walk and walk and feel that we are approaching something. We can feel body and soul growing. That is our emergence. As something is dissolving from our body and from our mind, something new is being added. Our feet bump into rock and stone and bleed. Our clothes cling to bushes and tear. Hands and face hurt themselves on thorny herbs. Tiredness overflows our entire body. In those moments when we believe everything is over, our comrades give us support.

Then, in the middle of the darkness, someone holds our hand and pulls us slowly behind him/her. Another shares his/her bread, gives a sip of water. Our path takes us to a river. Everyone jumps to the other side. But we don’t make it. We don’t dare, we don’t trust our feet. Then the friends on the other side of the river stretch out their arms and call out to us. We pause for a moment, gather all our strength, take a deep breath and then jump. We are already on the other bank. We dared to jump! Who would have believed it! As we continue walking, we feel a change in our feet.

They start to find their way by themselves in dark nights. We can’t believe it. Are these our feet? From now on our eyes see everything, our ears hear every sound. After our body, our heart begins to change. Also our desires, our dreams change. We see our own dreams now. We can really feel body and soul. Now we are ourselves! Our soul has left its shell. Our body has freed itself from its chains. Our dreams belong to us. And the path we walk is ours. It will lead us to new horizons. As we walk along the paths of the mountains with excitement, we see horizons that we have never seen, never could have seen on the streets between concrete buildings. This is the moment when we realize that the horizon is not a line in the distance.

The higher we climb, the more we realize that the horizon is never the same and always waiting to be discovered. Every mountain we climb offers us a different horizon. In the mountains every sunset is unique. No day is like the other and ends like no other. Nothing is repeated here. Because we have discovered that behind every mountain we climb there is a different horizon.

For us Kurds, walking and moving is something new that we are learning. We learn to build up distances and take steps forward. For the first time we try to open new ways and to move forward on our own way. After thousands of years of walking through the streets of civilization, we leave their labyrinths for the first time. For the first time we escape from our labyrinths and look to our own horizon. This our own way, our attitude and our view of life is something we no longer give away after all we have experienced…