We publish part one of the report written by Vala Francis following her return to the UK. Francis went to Turkey with a delegation of observers of the elections last May.

As part of an international delegation of observers for the presidential and parliamentary elections on 14th and 28th May, I went to the south-eastern regions of Turkey, northern Kurdistan. I observed the elections alongside parliamentarians, activists, lawyers, academics, students and trade union representatives from Scotland, England, Germany and Switzerland.

When I flew in to London on my way back, I was detained by counter-terrorism police and interrogated for three hours under special legislation that, unlike any other condition of questioning, does not give a right to silence. Under Schedule 7 of the Terrorism Act 2000, the police have the legal right to passwords for any technology, or else the detained person can be prosecuted for up to two years in prison. My phone and laptop were confiscated for analysis. After the interrogation, MI5 turned up for an ‘optional’ line of information gathering.

So what does British counter-terrorism have to do with international scrutiny over whether Turkish elections are free and fair?

We spent weeks following the campaign trail of the Green Left Party, (YSP - Yeşil Sol Parti), the new Kurdish-majority parliamentary party that took over from the Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP - Halkların Demokratik Partisi). HDP faces a closure case in the Turkish courts, and thousands of its members are in prison. YSP calls for women’s rights, democratisation of every layer of society, protection for minority languages and cultures, and a centre on ecology. Their politics are critical of the government’s shift towards the right, towards the enforcement of religious conservatism, and intensive war policies.

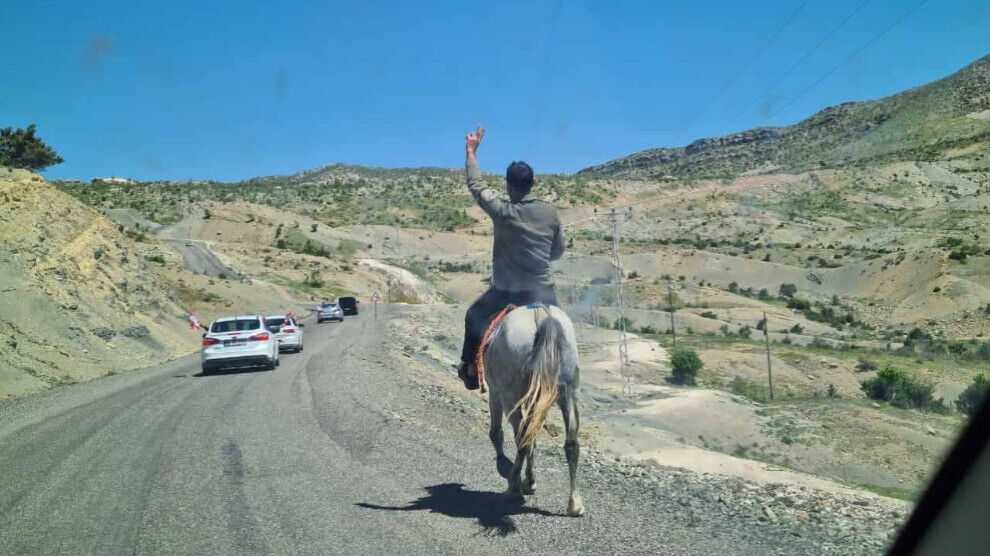

We drove to rural villages in convoys, attended weddings and danced traditional govend with the families, attended language and cultural rights events, and visited factories and shops. In the countryside, children would pour from the houses, run alongside the cars and beg for the multi-coloured YSP flags. Men sat on tractors and women from balconies would raise their hands to make the ‘victory’ sign, famous as a regional symbol of resistance against colonialism.

Ceylan Akça, member of the Turkish parliament from Yeşil Sol Parti, told us “elections are not only the days of voting, but everything that happens before hand is part of it. And nothing about this was free.” An intensive propaganda campaign is undertaken – according to Turkish media monitoring, Erdoğan had almost 33 hours of airtime on the main state television channel, compared to 32 minutes for Kılıçdaroğlu. This is backed up by the closure of HDP - the second largest opposition party - and the seizure of its funds, the entrapment of people within the judicial system through constant waves of detention, and continuous military intimidation.

The day after I arrived in Diyarbakir, more than 130 people were arrested across the country in armed dawn raids. They were mostly lawyers, journalists, academics, artists that amplify Kurdish culture, and campaign workers. The Yeşil Sol Parti central office was alight with resistant energy; the routine program of campaigning in factories and shops in the city was cancelled.

An announcement was planned for 1pm in the local neighbourhood to denounce the politically motivated arrests.

I walked with local party members to the announcement area, which was pre-emptively surrounded by riot police and public order vehicles lurking in side streets. The police tried to stop the announcement from taking place, then allowed it; we marched, then were stopped by the lines of riot shields. Then, again, we were allowed to march, and then stopped; this repeated every few metres, with the crowd fragmented each time by security forces, and groups of people encircled.

Gülşen Koçuk from the all-women independent media outlet Jin News, when speaking about the criminalisation of the Kurdish media and freedom of the press, said “the ruling government never denied our news or what we said - but what they are objecting to, or reacting to, is the fact we make the news to begin with. They're against anybody speaking up”. She continued, “they take everything - even the mice for the computers. When my colleagues asked the police why did they do this, one police officer responded “well, we are just trying to stop you from functioning””.

A similar type of policing was used during a women’s language and culture day event that we attended, where dozens of local women in traditional dress were banned from holding signs and placards that called for the Kurdish language to be protected and respected, or from making slogans or undulations, and they were blocked from marching down the road.

Local people told me that one of the major reasons Kurdish people voted for Kılıçdaroğlu was in the hope that his presidency would bring some clemency to the nearly ten thousand Kurdish political prisoners. A pre-election deal between HDP and CHP promised the release of at least some of the prisoners in exchange for the backing of Kılıçdaroğlu’s presidency campaign. Ceylan Akça said that the mass incarceration “is isolating not just the people in prison, but also the political ideas they believe in”.

The British delegation travelled to the Hakkari region, an area that is cradled by the snow-topped southeastern Taurus mountains at the intersections of Kurdistan with Turkey, Iran, and Iraq. The day before the first election, I gravitated towards a group of women in the Yeşil Sol Parti office in Yuksekova, some of the only women in the room of at least one hundred people.

One woman grasped my hand and began telling me about her son, who was killed by the Turkish security forces. I realised that these women, faces adorned by the outline of pristine white scarves, were likely to be Peace Mothers – a local chapter of a nationwide organisation of women and family members who struggle for judicial accountability after their children, husbands or siblings are killed by security forces or counter-revolutionary groups such as Hezbollah.

The mothers accepted a proposal for us to pay our respects to their loved ones. After a short minibus ride to the cemetery, we moved grave by grave, story by story. Many headstones are laid in fragments, a practice of ‘punishing the dead’ – but also their families. They told us; “the police come here and destroy anything that says who the buried are. We replace the stones every time, but they come again and smash them.”

Some of those buried were guerillas from other parts of Kurdistan, whose bodies were not accepted by the Iranian state or who could not be reunited with their families in Syria. Others were simply unarmed civilians walking home in Yuksekova. Some were local youths that took up arms during the 2015-16 city wars, when an urban revolt by young political Kurds was crushed by state military sieges of multiple south-eastern cities and towns in Turkey, including Yuksekova. Many had suffered brutal torture before their deaths. Regardless of their origin, “they are all our children, and we are all their mothers” a young woman told us. We were solemn – just one day before the election, the responsibility the outcome had for opening up possibilities of justice was sharply pointed.

All night, the results rolled in, and the inability for either candidate to reach the 50% threshold hung like a weight above the town. In the cool night air, a crowd chanted slogans in the streets against state tyranny.

Yeşil Sol Parti went on to win three out of three parliamentary seats in Hakkari, despite practices such as hundreds of excess and unknown military personnel using rural polling stations, which we witnessed first hand. The third seat was contested as an AKP seat: eventually, it remained with YSP.

After Erdoğan’s clear lead on Kılıçdaroğlu in the first round, the belief in a change of president seemed extinguished. The mood that drew over the region was dark; while members in local party chapters continued to campaign, one taxi driver told me “I hope that Erdoğan will be defeated, but I don’t believe it” – something I would come to hear frequently over the coming weeks.

Thousands of votes were misattributed to the wrong parties, leading to an enormous recount process. In Diyarbakir, several examples were found of hundreds of votes that were recorded to be for YSP in the final counts were later administratively recorded for the far-right ultra-nationalist MHP.

Purgatory from 14 to 18 May

On 22nd May, when talking about the Kurdish movement, Minister of the Interior Suleyman Soylu told a conference of security forces that “the lawyers should be the target” because they are “carrying all the sedition”, in particular from the inside of prisons to people on the outside. Turkey remains one of the biggest jailers of journalists worldwide. Worldwide statistics for the detention of lawyers are not available, but The Initiative for Arrested or Prosecuted Lawyers & Human Rights Defenders says that ‘since 2016, in Turkey, 551 lawyers have been sentenced to 3356 years in prison over terrorism-related charges, mostly membership in terrorist organisations’.

Zeki Baran, co-representative of the political prisoner solidarity confederation TUHAD-FED said “This [harassment] is serious in terms of democratic expression - it successfully creates an atmosphere of fear, and it serves its purpose by making people silent. It's a psychological war rather than a physical war.”

In the five days directly preceding the second election, 182 people were arrested – mostly in dawn raids – predominantly under a counter-terrorism pretext in relation to the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), like almost every other political arrest of Kurdish people. Many of those arrested were directly working with Yeşil Sol Parti, including Ayşe Karagöz who was a parliamentary candidate in the first round of elections. On 29th May, dozens of homes in Yuksekova were raided by special operations police, who proceeded to beat at least one man to the point of hospitalisation in the process of arresting a number of local political men.