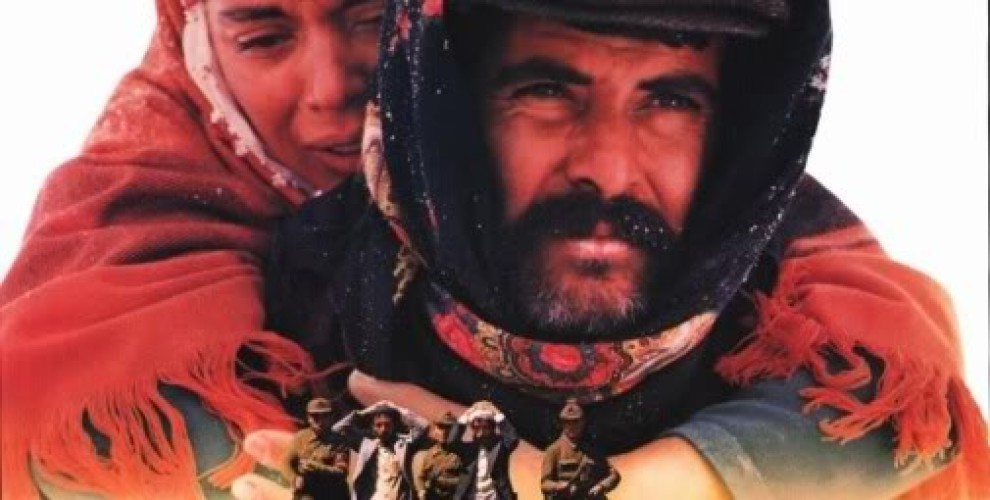

“The film Sürü (“The Herd”) is the history of the Kurdish people, but I couldn’t even use any Kurdish language in the film. If we had, everyone who acted in the film would have been imprisoned. Yol was dubbed in Europe, but even so, I couldn’t make it in Kurdish.” These are Yılmaz Güney’s words. He underlines these in an interview he gave to French journalist Chris Kutscher in 1983.

Güney attempted to use motifs to make the film Yol, which was edited in Europe, Kurdish. The vignette at the beginning that says “KURDISTAN” in capital letters is a sign of this.

Despite the issues in Güney’s accounts, the film Yol made cinematic history as a film to speak of all aspects of the tragedy Kurds have experienced. With both its political aspect, its storyline and its artistic aesthetics, the film is a masterpiece. It was banned in Turkey, and was smuggled to Europe to be edited and dubbed there, to be later screened in Cannes Film Festival. Yol shared a Golden Palm with Missing by Costas Gavras in Cannes in 1982. During the festival, Yılmaz Güney remained out of the public eye because he was wanted in Turkey, and Interpol had been notified. He was nowhere to be seen, until the awards ceremony in the festival.

“THE ORIGINAL YOL HAS BEEN BANNED IN TURKEY FOR 35 YEARS”

The film was banned in Turkey for a long time. In 1999, it was reedited by Fatoş Güney, and was shown in theaters again as a 1 hour 49 minute version, with some removed scenes. One of these scenes was one included in the Cannes 1982 version, put there by Yılmaz Güney himself: The Kurdistan vignette scene. It has been 35 years and the original film is still banned in Turkey.

Our goal here is not to give a lengthy account of the Yol film. Everybody has seen this film a couple of times in their life, or at least heard of its story. The film Yol was screened in the 70th Cannes Film Festival in the “Cannes Classic” category under the title “Yol - The Full Version”.

WHAT DOES DONAT KEUSCH AIM?

The new version of the film was prepared by Swiss producer Donat Keusch. Changes have been made to the color, the dubbing, and some others, making for a 1 hour 56 minute film to be screened in the Cannes Film Festival in the Bunuel hall. Compared to other classic films, the hall was almost full and there was a considerable interest. Editing the film into yet another version after 35 years created some questions though, and it is especially surprising that an organization such as the Cannes Film Festival accepted such a thing.

Producer Donat Keusch gave a speech before the screening and said that Yol is a Swiss-made Kurdish/Turkish film, and explained his motive as: “In 1982 in Cannes, we had to cut over 25 minutes from the film. After 35 years, I thought to restore it once more.”

But the question remains on what Keusch was aiming for when he remastered the film, and why he embarked on such a project. Because especially new footage and scenes used in this version are among those scrapped by Yılmaz Güney himself at the time. In particular, there are scenes with Süleyman from the Adana mafia, the sixth character who Güney scrapped because he didn’t fit the narrative. Other than the addition of 1-2 minute long scenes of gambling, prostitution and mafia relationships, there is nothing new or different in the film. The structure has been changed, and with new voiceovers, it’s almost like the film edited by Yılmaz Güney in 1982 has been tampered with.

WHY DID CANNES ACCEPT THE FILM?

Especially the removal of the “Kurdistan” vignette which was used by Yılmaz Güney but is removed in the new version, is surprising and suspicious. It makes one think, why did the Cannes Film Festival committee accept a tampered version of the film, 35 years later? One wonders which relationships led to the approval of this film.

NOBODY WILL BUY INTO THIS YOL

Nuray Şahin, who worked with producer Donat Keusch before in the new version of the film but later left the project due to disagreements, said she worked on the editing, dubbing of new scenes and other such heavy work, but was tricked by Keusch. Şahin said: “When I left, the Kurdistan vignette was still there. But they removed it after I left.”

Donat Keusch was asked why they removed the Kurdistan vignette after the screening, and defended himself: “This is the original of the film. I asked Yılmaz Güney, and that is what he said.” But everybody knows that Yılmaz Güney stipulated that the Kurdistan vignette is shown when the film was sent to the Cannes Film Festival in 1982. It is unclear why Donat Keusch removed the scene despite that.

Fatoş Güney also spoke to Alin Taşçıyan from Sanatatak about the new version of the film: “As a film reedited from footage Yılmaz filmed and then scrapped because he didn’t like them, it is first and foremost a great disrespect for an artist like Yılaz Güney, to his art and to his artwork. Especially editing a film out of parts Yılmaz refused to use, after 35 years, and claiming rights for it, is a matter that will be resolved by law. Me and my son Yılmaz will give the power of attorney to a legal group in Switzerland and resolve this issue in court. Because 50% of the rights to the film belong to Güney Films, of which me and Yılmaz Güney are partners.”

The film Yol will bring along much controversy, that much is certain. But it is also certain that cinema lovers won’t buy into this film made for commercial aims and populist concerns.