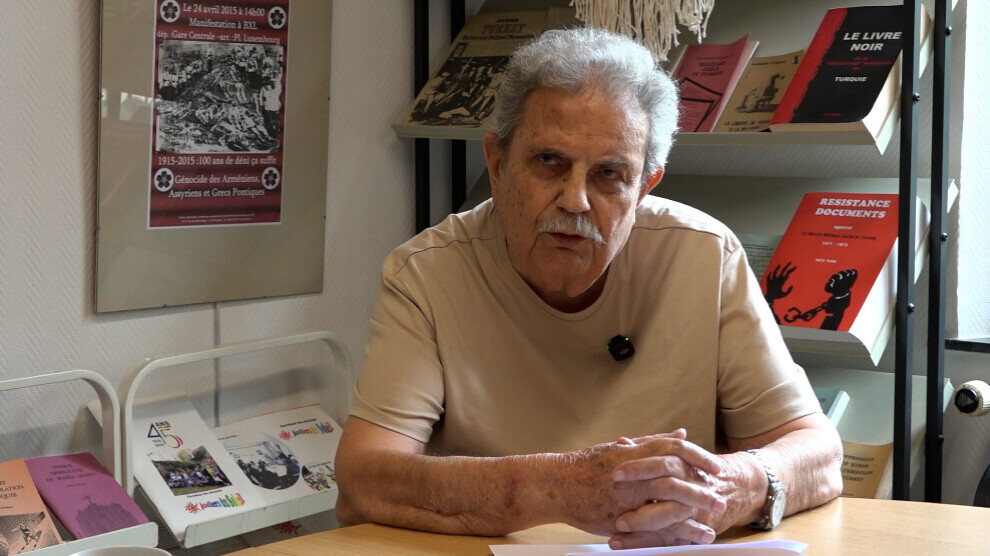

Özgüden: Social opposition must unite and act together

Doğan Özgüden criticized the government's reform package, calling for all opposition forces to unite and lead the process.

Doğan Özgüden criticized the government's reform package, calling for all opposition forces to unite and lead the process.

The reverberations of Abdullah Öcalan’s “Call for Peace and a Democratic Society,” issued on 27 February, are still being felt. Following this historic appeal, the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) announced on 12 May that it had decided to lay down arms, grounding its decision in Mr. Öcalan’s call.

In the wake of these significant developments, public attention once again turned to the government’s potential legal and legislative responses. However, the long-anticipated Judicial Reform Package, recently unveiled, has been widely dismissed by many as underwhelming, summed up by the phrase “the mountain gave birth to a mouse.”

Not only did the package fall short of public expectations, but government officials also declared that any substantial steps toward democratization in Turkey would be postponed until autumn.

Journalist Doğan Özgüden spoke to ANF about these latest developments.

In Turkey, current discussions about a resolution and political process focus on the lack of steps taken by the government. Most recently, the long-anticipated judicial reform package also failed to meet public expectations. How do you interpret this situation?

From the beginning, I have not viewed this issue with much optimism. I do not trust the state. The Turkish state, in its current form and with its present political leadership, does not inspire confidence in me. After a surge of public excitement following Devlet Bahçeli’s call, there were rumors that Abdullah Öcalan would address Parliament. That never happened. Even though the PKK held its congress and announced its decision to lay down arms in response to the messages sent by Öcalan, we have yet to see any of the developments we had hoped for.

What kind of developments were you expecting?

In my view, the first and most necessary step for the process to begin would have been the release of political prisoners, including Abdullah Öcalan and the executives of the Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP). But that did not happen. Most recently, we heard about a legal reform called the “Sentence Execution Package,” but that package did not result in Öcalan’s release, nor the release of other political prisoners.

Let us not forget that even our friends imprisoned due to their involvement in the Gezi Movement have remained behind bars for years. Now the government speaks of replacing the coup-era constitution. But even with all its shortcomings, the current constitution could allow for many significant reforms.

What do you mean by that?

This constitution clearly states: “The decisions of the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) are binding. The decisions of the Constitutional Court are binding.” Yet many of our friends remain in prison, even though there are court rulings ordering their release. Why? Because this constitution is not being implemented.

If a new constitution is to be drafted, it cannot be written by a group of 15 or 20 individuals handpicked by Tayyip Erdoğan to serve as his loyal gatekeepers. Such a constitution can only be legitimate if it is drafted by a constituent assembly, one that represents all democratic forces in Turkey. But even that may not be necessary. As I said, many of the current issues could be addressed under the existing constitution, if only it were enforced.

When it comes to the release of political prisoners, the argument we often hear is: “If we release these prisoners, then members of the Fethullah Gülen movement will have to be released as well.” Can you imagine anything more outrageous? If people are imprisoned for their political ideas, they must all be released, without discrimination.

At this point, there is strong emphasis on democracy, particularly as a necessary condition for resolving the Kurdish question. On the other hand, the government is also being accused of trying to divide the opposition. How do you see this?

This is one of the major uncertainties in the new process initiated by Devlet Bahçeli and seemingly supported, though in a stumbling manner, by Erdoğan. If we are truly talking about democratization, the issue must be brought before the Grand National Assembly of Turkey. Laws must be passed, and the necessary political decisions must be taken. But we are not witnessing such a process right now.

Despite the PKK’s congress decision to lay down arms, based on Abdullah Öcalan’s call, no concrete steps have been taken toward implementing this decision. Let’s say the PKK has committed to disarm, where will they lay down their weapons? How will it be done? Under what conditions? Is there any legal framework for this?

We have seen how this plays out in examples from around the world. In South Africa, for instance, when such matters arose, if a peace process was to begin between guerrilla forces and the central government, it required mediation by institutions with international legitimacy and authority. So far, I have not heard of any such mediating body being involved in this case.

You are emphasizing the need for a third party at the negotiating table, is that correct?

Yes, a third-party presence is absolutely necessary. There must be a neutral group of arbitrators capable of handling the issue objectively. There are many human rights organizations and respected individuals across Europe and the world who have long contributed to Turkey’s democratization efforts and who have never been enemies of the Turkish state.

But Tayyip Erdoğan currently sees himself as a mediator in international issues like Palestine and Ukraine. Because of this self-assigned role, he rejects all forms of external assistance or mediation in domestic matters.

I want to highlight something important here: I had hoped the Peoples’ Equality and Democracy Party (DEM Party) would enter this process with more preparation and determination. Instead, there was a rush to embrace the atmosphere of a peace process, even before key conditions were met. I respect the efforts being made, visits should be carried out, meetings should take place.

But we’ve reached a point where it almost seems as if Devlet Bahçeli and Tayyip Erdoğan have suddenly undergone a miraculous transformation and are now ready to resolve all of Turkey’s democratic problems and recognize the Kurdish nation’s historical demands. That, of course, has not happened.

What is your proposal in response to your criticisms? What should the opposition do to build democracy? What kind of stance should it take?

Beyond the DEM Party, the Republican People’s Party (CHP) also bears a great deal of responsibility. Where does the CHP stand on this matter? During his recent visit to the European Parliament, the CHP’s chairperson said nothing about the peace process.

I follow closely. So far, the only stance the CHP seems to have taken is to use the situation of Istanbul Metropolitan Mayor Ekrem Imamoğlu as a basis for launching a future election campaign. There is no serious engagement with the Kurdish movement.

The DEM Party, the CHP, and all democratic forces must come together. The same kind of mass mobilizations we saw in support of Imamoğlu should also be organized for the Kurdish and leftist political leaders who remain imprisoned today. Only through such an approach can a genuine democracy be built in Turkey.

In addition, the Kurdish movement exists not only in Turkey but also in Syria, Iraq, and Iran. There needs to be engagement with Kurds across all these regions. In Syria, the Kurdish movement gave thousands of lives fighting against ISIS, and now it is being targeted, this effort to crush it undoubtedly involves Erdoğan’s political calculations.

Let us not forget: the person currently acting as head of state in Syria is a former ISIS member. If democracy is to be established there, the Kurdish movement must be included in governance in a federal structure. In my opinion, the Turkish state must not obstruct this.

Are you suggesting that developments centered in Syria are connected to the peace process in Turkey?

Undoubtedly, they have an impact. I remember both Devlet Bahçeli and other members of the government explicitly stating that the Kurdish movement in Syria should also disarm. This has been repeated many times and continues even now. However, in my view, the Kurdish movement in Syria is an autonomous force struggling to defend itself and to transform Syria into a democratic country. This fact should not be ignored.

What would you like to say about building a democratic society? Independent of institutions and political parties, what responsibility does society itself bear as a subject in this process? How should it approach democratization?

The opposition in Turkey is not limited to the DEM Party and the CHP. As someone who lived through the 1960s, I remember well: since the fall of the Democrat Party, all human rights organizations, professional associations, and other such forces must come together. If a constitutional change is to happen, or if there is to be any transformation in Turkey, it must be carried out by a united front that includes all these sectors.

Today, there are diasporas across the world that originate from Turkey: Kurdish, Armenian, Assyrian diasporas, and many political exiles. What is needed is the formation of a large, inclusive movement in which all of these communities can participate.

Of course, the DEM Party holds the legitimate right to lead this process. It is the legal and institutional representative of democratic struggle within Turkey. But it must engage with all these forces and help guide this process forward.