The past and present of Druze and Alawites in Syria - Part Two

The Nusayris adhere to the Twelver branch of Shia Islam.

The Nusayris adhere to the Twelver branch of Shia Islam.

The social fabric of Syria includes a Muslim majority, with approximately 85 percent of the population being Sunni Muslims, alongside Alawites (Nusayris), Shia Muslims, Druze, and Ismailis.

Arab Alawites (Nusayris)

The faith community known as the Nusayris adheres to the Twelver branch of Shia Islam. This belief system is thought to have emerged during the period of the eleventh Imam, Hasan al-Askari. After Imam al-Askari’s death (d. 873), a new religious current developed through the teachings of Ibn Nusayr and his followers. Originating as a branch of Shia Islam centered in Iraq, it later spread and took root in Syria (then known as the Levant). As with the Druze, the ethnic origins of the Nusayris are based on abstract and unverifiable sources, and no definitive record exists. Some Alawite sources claim that they are descended from settlers who came from the region of Mount Shengal (Sinjar) in the 13th century.

Each of the Nusayri leaders who followed Ibn Nusayr contributed new rules and rituals to the belief system, gradually shaping it into its current form. The figure who most significantly organized and reformed Nusayrism was al-Hasibi. Over time, the term “Nusayri” became less commonly used and was gradually replaced by the term “Alawite.” After Syria came under French mandate, the community began identifying itself more often as Alawite rather than Nusayri. Some Alawite intellectuals also chose to adopt this identity. In fact, some argue that the term 'Nusayri' gradually acquired derogatory and humiliating connotations over time.

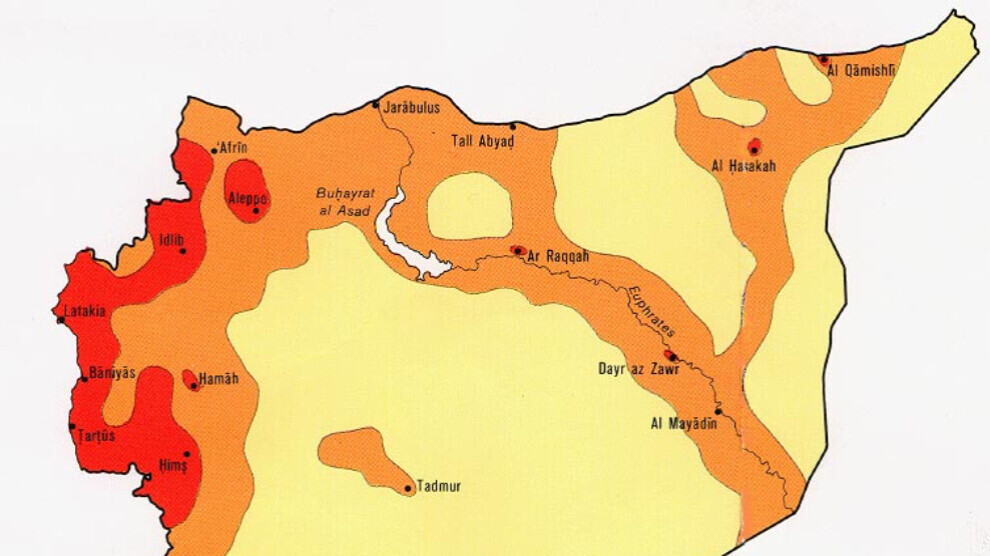

There is no definitive data on the total population of the Nusayris, as population censuses are not conducted based on sectarian affiliation. However, estimates suggest that the Nusayri population may be around 3 to 3.5 million. Within the fragmented geography of modern nation-states, Nusayris make up approximately 10 to 12 percent of Syria’s population (nearly 3 million people). They are concentrated mainly in Latakia, Tartus, the rural areas of Hama and Homs, the western part of Idlib, and to a much lesser extent, in Damascus and Aleppo.

In Turkey, it is estimated that between 400,000 and 500,000 Nusayris live in the Hatay region, especially in Samandağ, Arsuz, and Altınözü, as well as in smaller numbers in cities like Adana and Mersin. A very small Nusayri population is also said to exist in northern Lebanon and parts of Jordan. These figures, of course, reflect estimates from before the outbreak of the Syrian civil war.

The Nusayris diverge significantly from classical Shia Islam. They regard Ali as a divine being. Their beliefs are strongly influenced by mystical (Sufi) elements. The transmission of religious knowledge within the community is limited, and the dominant belief is that there are esoteric teachings kept hidden, which makes the details of the faith largely unknown and closed to outsiders. While Islamic traditions are observed, they are practiced in distinct ways. Rituals such as prayer and fasting are performed according to their own interpretations. The belief in reincarnation (transmigration of the soul) holds particular significance within Arab Alawite spirituality.

One of the defining aspects of their social life is their closed communal structure. Marriages are typically arranged within the community. Women enjoy relatively greater freedoms compared to many surrounding communities. Their religious leaders, known by titles such as Dede or Sheikh, hold a respected place within society and are responsible for transmitting religious teachings.

At the core of their belief system is a sacred triad known as the “Ana Inanç” (Main Belief), consisting of Mana (Meaning), Ism (Name), and Bab (Gate). They believe that the divine reveals itself through this triadic structure. Mana represents Ali, Ism corresponds to Muhammad, and Bab is symbolized by Salman al-Farsi.

Since its emergence in the 9th century, the Nusayri faith has never had the freedom to develop in peace and has continuously been subjected to pressure. It has diverged from classical Shia Islam in many ways and has often been marginalized as a result. The Nusayri population has mostly lived in mountainous regions, often in rural and agricultural communities. Throughout history, they have rarely received the recognition or support they deserved. Because of their faith, they have lived under constant pressure as a persecuted minority.

Under Ottoman rule, the Nusayris were excluded, oppressed, and subjected to systematic injustice. They were allowed no real opportunities beyond supplying soldiers and paying taxes. Even their worship practices had to be conducted in secret. The faith is characterized by its esoteric nature, assigning deep symbolic meanings to what lies beneath the surface, truths, mysteries, and hidden realities.

After the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and during the period of the French mandate in Syria, the Arab Alawites gained limited recognition. While plans were made to establish states for other minority groups in Syria, the Alawites were excluded from such provisions. However, at least on paper, the regions they inhabited were officially acknowledged as "Alawite territories."

Their fate did not significantly improve under the Ba'ath regime. When Hafez al-Assad, himself an Arab Alawite, came to power through the military coup of 1970, the historical marginalization of the Alawites remained largely unchanged.

To avoid confusion between the two branches of the Ba'ath Party, it is useful to briefly explain the distinction. The Ba'ath Party, originally founded in Syria, later established a branch in Iraq. Though initially a single party, internal contradictions led to a split. The Iraqi branch eventually evolved into a separate Ba'ath Party, often operating under the control of Sunni leadership. Ironically, what began as a unified political movement turned into two mutually hostile parties. In Iraq, the Ba'ath Party became a vehicle for a Sunni minority ruling over a Shia majority, while in Syria, it turned into a party led by Alawites governing a Sunni majority. The two states would eventually go on to accuse each other of betrayal and deviation from Ba'athist principles.

When Hafez al-Assad took over the Syrian branch of the Ba'ath Party, there was strong backlash from the Sunni population, which led to serious protests. At the time, the Syrian Constitution stipulated that only a Sunni Muslim could serve as president. In response, and to calm public outrage while preserving his hold on power, Hafez al-Assad appeared with the Grand Mufti of Damascus and prayed at the Umayyad Mosque, publicly declaring himself to be a Sunni. This marked one of the earliest moments when anti-Alawite sentiment began to take shape within Sunni circles. As seen in today’s massacres targeting Alawites, the roots of such violence cannot be solely attributed to the Assad regime, it existed long before.

In the government established by Hafez al-Assad, the majority of ministerial positions were assigned to Sunni officials. Although he was born an Alawite, Assad officially changed his religious identification and formed a cabinet composed almost entirely of Sunnis. Rather than elevating the broader Alawite community, power and privilege were restricted to Assad’s immediate family circle and that of his wife’s family, only two families benefitted from the state's resources. These individuals typically held key positions within the military and intelligence apparatus.

Although Hafez al-Assad rose to power with support from the Arab Alawites, their general situation did not improve significantly under his rule. There is also a widespread misconception surrounding this reality. The notion that the Assad regime is “Alawite” in character is misleading. In truth, the Assad regime is a Sunni administration headed by an Alawite figure. As such, the Alawites remained a marginalized and neglected community even during his rule. They were largely confined to remote rural areas with little infrastructure or public services.

In the military coup he carried out in 1970, Hafez al-Assad brought the minority groups that had supported him under tight control. The Alawites, Druze, Ismailis, and Christian minorities were among Assad’s most significant backers. However, all of these communities were ultimately excluded from real power, placed under surveillance, and subjected to various forms of repression.

The Alawite community in Syria has also endured pressure from the Sunni majority due to their beliefs. They have been regarded as religiously illegitimate and targeted as such. The Sunni backlash against Assad frequently took the form of hostility toward Alawites, not because of political actions, but because of religious differences. The portrayal of Alawites as supporters of Assad and the justification of violence against them on these grounds is a gross distortion. At the root of attacks that amount to acts of genocide lies deep-seated sectarian hatred.

A serious sociological examination of the Alawite community reveals that their historical fate has remained largely unchanged since the emergence of the Nusayri faith in the 9th century. Although they originated as a breakaway branch from Shia Islam, they were later excommunicated from classical Shia doctrine as well. As a minority in every region they inhabited, they were consistently subjected to persecution. Under the control of external powers, they were never able to establish any significant presence or autonomy. This pattern did not change even under the Assad regime, which is often mischaracterized as an Alawite administration. In fact, the situation deteriorated further under Bashar al-Assad compared to his father’s rule.

When power shifted hands in Syria, the door was opened for Salafi–Takfiri–Jihadist forces, who view the Alawites (referred to as “Rafida”) with hostility, to carry out mass killings and campaigns of extermination. These massacres of Alawites are less a product of Assad’s regime than they are the result of deep-rooted Sunni hostility toward Shia communities.

The Alawites, who have been largely confined to Syria’s coastal strip, are more vulnerable than other communities due to their relatively limited organizational structures. Reports indicate that the number of Alawites killed in attacks by HTS has reached around 50,000. This figure is comparable to the number of Palestinians killed in Israel’s assault on Gaza, yet it occurred in a much shorter time span. News sources also report that nearly 100,000 Alawites have taken refuge in Lebanon.

In conclusion, it must be stated clearly that the current administration of HTS in Syria poses a grave threat to minority rights and religious freedoms. HTS is a continuation of the ISIS structure. Regardless of the name it operates under, its structure, mentality, and practices are identical to those of the ISIS. This warning also applies to the Kurds, who are considered the most organized among Syria’s communities. The threat remains constant. For all ethnic and religious minorities in Syria, danger is inevitable under HTS rule. In order to confront this threat, they must organize among themselves and fight to gain the right to represent themselves in Syria’s future.

Large population groups such as the Kurds, Alawites, Druze, Ismailis, and Christians must absolutely build organizational structures from within, defend themselves through legitimate means, and ensure their rights are protected under a new constitution, one in which they can express themselves and participate in decision-making processes.

Looking ahead to Syria’s future, instability and conflict appear more imminent than ever. It is essential to be prepared now for the chaotic developments that lie ahead, taking into account both internal and external dynamics.