Arbo, a village near Nusaybin district in the province of Mardin that is hardly known today, is once again coming to the forefront of history more than a century after the genocide of the Syriacs. During renovation work on the Mor Dimet Church, the largest of the village's seven churches, residents stumbled upon a mass grave; numerous skulls and bones stored in an underground vault deep beneath the altar area.

What initially appeared to be an archaeological find turned out to be a gruesome echo of history: The remains most likely belong to victims of Sayfo, the genocide of the Syriac, Assyrian, and Chaldean religious communities during World War I—or from an earlier wave of violence in the 19th century under the rule of the Kurdish ruler Êzdîn Şêr (Izz al-Din Shir or Yozdan-Shir). For many members of the now scattered Syriac diaspora, these are not just bones. They are the last traces of their ancestors, silent witnesses to a repressed chapter of history.

Between two eras of violence

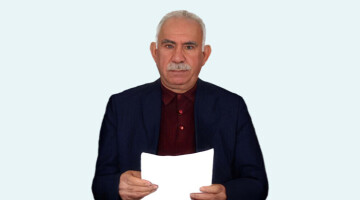

Historian and author Yawsef Beth Turo sees a dual historical significance in the recent discovery. In his opinion, the remains could be attributed to two periods: on the one hand, the repression in the 19th century under Êzdîn Şêr, who cracked down on tax-evaders among the Syriac villages, and on the other hand, the systematic extermination of Syriac Christians in 1915 by Ottoman troops and allied Kurdish militias.

According to Beth Turo, these findings are not just historical traces but also symbols of two major ruptures that remain alive in the memory of the Syriac community.

Historical background of the Syriac genocide

Speaking about the genocidal campaign against the Syriac community in 1915, researcher Beth Turo noted that the genocide was first directed against Armenians and then the Syriac community became a target. “The process that started in April 1915 was first directed against the Armenian people. However, as of May and June, it spread to the eastern provinces and included the Syriac community. The attacks in Urfa, Malatya, Harput, Diyarbakır, Mardin, Nusaybin, Hasankeyf and other towns eventually reached the Tur Abdin region.”

Beth Turo stated that very violent attacks were carried out in Tur Abdin between June and August in 1915: “Not only the army, but also local armed groups and some structures that consisted mainly of Kurds and gangs were involved in the attacks. The Syriac population was largely destroyed by these attacks.”

Still, Syriacs in Tur Abdin put up organized resistance at six different points, said Beth Turo and continued: “One of them was the village of Ayn Wardo (Gülgöze), the other was the village of Hah (Anıtlı), the third was Mount Bagok, also known as Tur İzlo, the fourth was the village of Bsorino (Haberli), the fifth was Azax, today's İdil, and the sixth was Dyro du Slibo (Çatalçam). In these places, Syriacs resisted and stood against the genocide.”

Beth Turo pointed out that the vast majority of Syriacs living in Tur Abdin today survived thanks to these six points of resistance. “However, there was great destruction in other settlements in the region. Over 90 thousand Syriacs were massacred in and around Tur Abdin alone.”

‘Remains discovered at Arbo mark two major historical breaks’

Drawing attention to the historical background of the bone remains unearthed under the Mor Dimet Church in Arbo village, Beth Turo emphasized that these remains point to two different periods:

“There are two views on these bone remains in Arbo village,” Beth Turo said. The first narrative dates back to the period of Êzdîn Şêr, one of the Bedirxanîs, in the 1800s: “During the reign of Êzdîn Şêr, residents of the village of Arbo who refused to pay taxes were persecuted. In order to suppress the villagers who fought back, Êzdîn Şêr gathered forces and set up a tent near the village. Although the date is not certain, it is said to be in the 1800s.”

“During the attack on Arbo, Êzdîn Şêr was confronted by Sallo Beth Cırdo, one of the Syriac leaders at the time, and fierce clashes broke out between them. Many people from both sides lost their lives. The victims were buried en masse without ceremony. After a long time, the bones and skulls were collected and buried in the church to restore dignity and respect to them.”

Emphasizing that the village of Arbo is a symbol of resistance for the Syriac community, Beth Turo said, “Arbo was, of course, an active village and its people’s sphere of influence extends from Tur Izlo to the villages near Cizre. The residents of Arbo village and Syriacs are known in the region for their courage and resistance. They are absolutely unafraid and unyielding. It is known as a village that resists the Kurdish, Turkish and Yazidi attacks around them.”

In addition to the Ottoman detachments, the village was attacked by Omariyan, Bunisri, Aliyan, Afşe Yazidis, Mihokan and Dasikan Kurdish tribes. The attacks continued for 15 days, marked by heavy clashes. During the fighting, Hesenê Haco was even trapped in a house with his gang of 15 men. This information reached Saruhan Agha and they were released upon his request. Saruhan Agha was one of the few Kurdish notables at the time who had the best relations with the Syriacs. The release of Hesenê Haco and his gang was seen as a sign of the goodwill of the Syriacs and the fighting stopped after 15 days.

In that period, there is a mention of Syriac heroes named Lahdo Be Sino, Hapsuno d'Be Arsan, Lahdo Golo, Isa d'Be Arsan, Eliyo d'Be Eliko, Shemcun d'Be Sacdo d'Be Panjaro, Gallo d'Be Mushe, Musa d'Be Xarbanda wu Zaytun d'Be Romanos. These are mentioned in the book 'Sayfo 1915 and the Genocide' written by Suleyman Hınno, Pastor of Arkah - now Üçköy.”

Women and children dying from epidemics and disease

Beth Turo also gave information about the massacres against women and children at that time: “Pastor Suleyman Hynno, in his work I mentioned, says that Syriac women and children were sent to Mor Malke Monastery and took refuge there. Of course, the real losses were suffered mostly after Sayfo because both hunger and epidemics broke out after Sayfo. Many Syriacs lost their lives in the monastery, in Ehwo and Badıbbe. When some Syriacs returned to Arbo, they died there due to the epidemics. The people who lost their lives were buried en masse. Years later, these bones and skulls were collected again and buried in Mor Dimet Church as a restoration of honor.”

The place of shelters in the memory of the Syriac community

Beth Turo added that the writings on the 1915 Genocide have gained significant momentum in the last 10-15 years, and it was very difficult to address these issues in the past. However, recently, both Kurdish and Turkish writers, together with Syriac writers, have shed more light on this issue. “The role of Kurds as well as Turks in this genocide is being questioned, criticized and condemned. Such confrontations are very important and valuable steps for both the Kurdish movement and the brotherhood of the Syriac, Kurdish and Turkish peoples.”

Emphasizing that the shelters harbor heavy traumas in the memory of the Syriac community, Beth Turo said, “In 1915, many Syriacs both survived and lost their lives in these shelters. There were losses due to epidemics or shelters being set on fire. Such structures opened deep wounds in the memory of the community. These stories, passed down from generation to generation, are still vividly alive in our memory despite the passage of 3-4 generations. When such shelters come to light, the events of 1915 immediately come to life and the pain is renewed.”

Beth Turo reminded that during the genocide, the number of Syriacs living in the Ottoman lands decreased from 950 thousand to 300-350 thousand, and 90 thousand people lost their lives in and around Turabdin alone: “The attacks were not only carried out by the Ottoman army, but also with the support of local Kurdish tribes and gangs. Had the Kurds remained neutral during this process, destruction on this scale would not have occurred. Unfortunately, many Kurdish tribes actively participated in these massacres. For this reason, the Syriacs also developed resentment towards the Kurds. Because the Kurds were our neighbors, we lived together; we did not expect this from them.”

On the other hand, Beth Turo stated that the self-criticism coming from the Kurdish political movement in recent years has positively affected the Syriac community. “Many personalities, from Selahattin Demirtaş to Ahmet Türk, from Mr. Öcalan and other Kurdish leaders, have pointed out the negative role of the Kurds in this process. These statements contributed to the Syriacs developing a more constructive approach towards both the Kurdish people and the Kurdish movement.”

Repression policies during the Republic and the position of Arbo

Yawsef Beth Turo noted that assimilation policies against Syriacs intensified after 1915, with the proclamation of the Republic. He continued: “Many forms of pressure were applied, including changing place names, the surname law, the closure of schools and invisibility in public life. Most recently, in 1928, the Syriac private school in Mardin was closed. Although we were recognized as a minority in the Treaty of Lausanne, these rights were not implemented. Syriacs were intimidated, silenced and forced to migrate en masse.”

Beth Turo pointed out that the village of Arbo was also evacuated three times during this period, which is a typical example of the oppression and displacement policies against Syriacs.

A great opportunity to confront the past

Yawsef Beth Turo stated that the unearthing of such shelters is a great opportunity to confront the past and strengthen collective memory. He added: “The contribution of Kurdish and Turkish writers to the questioning of their roles in 1915 is very valuable in terms of a historical confrontation. I hope that these steps will increase and deepen.”