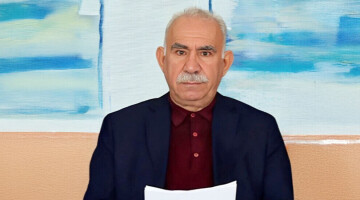

Özgül Saki, a member of parliament for the Peoples' Equality and Democracy Party (DEM Party), who closely follows women's struggles and self-governance experiences in various parts of the world, evaluated the ongoing peace struggle in Turkey for ANF in light of similar processes in other countries.

Zapatistas closely follow the Kurdish freedom movement

Özgül Saki provided examples from global experiences and shared her observations and insights as follows:

"There is considerable knowledge and experience across different regions of the world concerning conflict resolution and self-governance processes. All these experiences show us that there is no single roadmap or formula. Each geography and each period has its own specific solutions, forms of organization, and methods of struggle.

The publications of the DEMOS Research Collective, which conducts broad studies on peace processes and examines examples from both Turkey and around the world, offer highly valuable content in this regard.

Additionally, the research series titled ‘Conflict Resolution and Peacebuilding: Global Experiences’ prepared by the Diyarbakır Political and Social Research Institute (DISA) is one of the most comprehensive works in this field.

Between 2017 and 2020, I spent about a year and a half in Guatemala, Chiapas, and Colombia to witness and, if possible, to contribute in a small way to the struggles there. These experiences gave me significant insight into conflict resolution and peacebuilding. The armed struggle period of the Zapatistas, a guerrilla movement, was relatively brief compared to Colombia and Turkey. However, what they have built on their lands since the 2000s under the motto ‘Otro Mundo es Posible’ (Another World Is Possible) is truly impressive. Despite all threats and pressures, an autonomous and self-governed social system has survived to this day. I even wrote a short piece about my initial experiences there shortly after my first visit.

At first, I was quite surprised to see how closely the Zapatista movement, located thousands of kilometers away in a completely different geography, follows the Kurdish Freedom Movement. As the imperialist-capitalist system spreads like a nightmare over peoples, the Zapatistas seek both inspiration and solidarity networks while advancing their own revolution. I observed how they constantly emphasized the significance of the Rojava Revolution to them, and my initial surprise eventually turned into understanding.

The way Zapatista women organize themselves in both the guerrilla struggle and in socio-political life, and their development of a women's liberation perspective, bears remarkable similarities to the Kurdish women’s movement and its Jineology philosophy. This could be the subject of a separate interview in itself.

Shortly after the San Andrés Agreement was signed between the Mexican government and the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) in February 1996, the Zapatistas announced that they would no longer engage in armed actions. They declared, ‘We have chosen life over death. Instead of stockpiling weapons, we chose to build schools and hospitals and to improve our living conditions,’ and began constructing an autonomous, communal social life on their land.

From 1994 to the signing of the San Andrés Agreement in 1996, contrary to popular belief, it was not Subcomandante Marcos, but Comandante Ramona who sat at the negotiation table. During every phase of the negotiations, the Zapatistas held meetings within their communities to evaluate developments and then made collective decisions before returning to the table. In this sense, they experienced a unique process.

Although some of the demands of the indigenous peoples were partially met in the agreement, the Mexican government failed to implement it. Nevertheless, the Zapatistas began establishing their own governance structures within the framework of the agreement. Since then, they have continuously adapted their organizational structures to the needs of the times, maintaining an autonomous, self-governed life in Chiapas based on collective ownership and equal representation of women. In this sense, I can say that their political orientation closely resembles the democratic society model of the Kurdish Freedom Movement.

In peace processes, persistence is essential despite challenges

In September 2016, after fifty-two years of conflict and four years of peace negotiations, a peace agreement was signed between the Colombian government and the guerrilla organization FARC (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia). The peace process was conducted under six main topics: land reform, political participation, disarmament, addressing the issue of illegal drugs, victims' rights, and implementation of the peace agreement.

Considering both the lengthy armed struggle and the developments over the years, it is possible to draw parallels between FARC and the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) in terms of FARC's repeated unilateral ceasefires, the highly violent phases caused by changing actors within the Colombian government, the continuation of bloody clashes even during negotiations, and the tactics pursued in their guerrilla struggle.

In light of these experiences, it is not easy to quickly summarize what needs to be done in the new negotiation phase that began in Turkey in October 2024 with Devlet Bahçeli's call, especially when the memories of the 2013-2015 negotiation period and the severe repression and violence that followed are still fresh, and when many political actors and comrades from that period have been sentenced to decades in prison. There is no definite formula, but it is essential to set basic principles.

The Colombian negotiation and peace process is considered a success partly because both sides largely adhered to the terms of the signed agreement. For this reason, it can serve as a guiding experience for us as well. The final peace process in Colombia lasted about four years. It is known that some undisclosed contacts took place between FARC and the government prior to those years. During the past four years, the topics discussed at the table have been simultaneously debated in forums across many parts of the country, and the demands of all segments of society affected by the conflict have been submitted to the delegations in the form of reports. This offers a very strong example of how peace can be socialized.

When I arrived there, two years had already passed since the signing of the peace agreement, but none of these organizational structures had dissolved. Every step taken after the agreement was closely monitored. Serious issues still remained, particularly regarding land reform and the demands of indigenous peoples. The safe return of peasants to areas vacated by the disarmed FARC guerrillas had not been fully ensured, and in the resulting vacuum, paramilitary forces began to settle in those regions. I attended a large two-day meeting in a village where this problem was discussed. At this gathering, which explored options including rearming to defend their land and decided to build solidarity networks, strong criticism was directed against both FARC and the government.

What I am trying to emphasize is that peace, negotiation, and resolution are not matters that can be settled within a few months. More importantly, in the absence of strong self-organizations, gains can easily be retaken at any moment. Therefore, when it comes to the question of ‘what we should do in Turkey,’ we must not leave peace solely to the government’s initiative. We need to quickly build organizations that ensure the political participation of all segments of society in the process. Just as was done in Colombia, we must organize forums and discussions at this stage to collectively address concerns and anxieties through political engagement.

We also know that this negotiation call came at a point where the People’s Alliance (AKP-MHP) was compelled to recognize its inability to defeat the Kurdish Freedom Movement, in the face of shifting power balances in the Middle East and the emergence of Israel as a permanent force in Syria. Undoubtedly, this is a very significant step and has considerably expanded our political space for action.

At an international conference on peace processes two weeks ago, a participant from Kenya said: 'In times like these, it is very comfortable to be pessimistic and say nothing will come of this, because then you do not have to do anything. The difficult part is to remain persistent in the pursuit of peace despite all risks and to continue the struggle. That is the most basic necessity.' Indeed, the challenge lies in moving swiftly away from a passive stance that waits for actions from the government, establishing social networks where all sectors can develop their own peace plans, and preparing for a long-term political process."

The persistence of Kurdish women in peace is crucial

Özgül Saki emphasized the importance of Kurdish women's persistence for peace and stated: "In the heart of a war zone, the resolute efforts of Kurdish women for peace and their continuous calls to women in Turkey to join the peace struggle are directly connected to their awareness of the severe destruction that war inflicts on the lives of all women. Moreover, this insistence stems from their understanding that it is not enough for women to merely support peace processes. A permanent peace requires women to participate in the struggle as decision-makers and builders with a political presence.

This solidarity, which began in the 1990s with the campaign ‘Do Not Touch My Friend’ and continued with the establishment of the Women’s Initiative for Peace in 1996, was revived in 2009, becoming more organized despite some interruptions. The report prepared by the Women’s Initiative for Peace during the negotiation period that began in 2013 continues to serve as a highly instructive document on how we can participate in the process with a clear perspective in the current period.

Since then, the quest to strengthen the joint struggle where the fight against patriarchy and the struggle for peace intersect has never ceased. Today, the establishment of the ‘I Need Peace Women’s Initiative’ marks a new threshold for all of us. This initiative has announced itself through an action that presents urgent demands to the public, such as decriminalizing politics, ending cross-border military operations, halting special security zone practices and military deployments, removing all government-appointed trustees, and repealing Decree Law No. 674 that paves the way for these interventions. In doing so, the initiative has begun to pave the way for an honorable peace.

Women who insist on peace continue to organize, fully aware of the difficulties ahead and recognizing the need for international solidarity."

The Kurdish women's peace struggle has reached all women

Özgül Saki pointed out that the peace struggle led by Kurdish women has reached other women, emphasizing the importance of organized struggle. She continued:

"The voice of this struggle is actually reaching all women. The words of Eren Bülbül’s mother, whose son died after being forcibly taken by soldiers into a conflict zone in the Black Sea region, are very telling. She said, ‘If no one else is going to die, then there must be peace.’ This tells us a lot. Yes, Turkish mothers also want peace sincerely. However, it is unfortunately not possible to overcome in a short time the antagonism created by a century of policies of denial, destruction, and assimilation.

We also need to seriously reflect on why a strong anti-war movement has not been established in Turkey. In an environment where we can speak freely and where democratic processes are allowed to function, we would witness how strong the demand for peace can become. In a historic moment when right-wing, fascist, and authoritarian regimes are gaining power worldwide, our task is not easy. However, organized struggle is essential for the socialization of peace."

The women’s movement has begun to take steps in line with peace efforts

Özgül Saki described the PKK’s decision to lay down arms and dissolve itself as an important stage for expanding the peace struggle, noting that the women’s movement as a whole has begun to take significant steps toward supporting these efforts. She concluded: "The PKK’s disarmament and dissolution hold the potential to broaden the scope of peace negotiations in Turkey. However, this is not an outcome that can occur spontaneously. A government that boasts about being the second-largest army in NATO has in fact admitted that it cannot achieve its goals through military means. This is a very difficult reality for them to accept, which is why they avoid using the terms resolution, negotiation, or peace. If you pay attention, they uniformly refer to it as the ‘Terror-Free Turkey Process.’ The terminology matters. This expression can also be interpreted as an attempt to reframe the Kurdish issue solely as a security problem, thereby seeking new legitimacy without taking any political or societal steps.

At the same time, international support for the PKK’s dissolution and the 'Call for Peace and Democratic Society' continues to grow, and it is strongly embraced by various segments. Now it is necessary to expand the struggle in the political and social spheres, to organize within class struggles and youth movements, to intensify actions and activities that pressure the government to take real steps, and to establish effective cooperation with all political groups that have declared their support for this process.

As we said at the beginning, building peace is a very serious task. It cannot be left to the will of the government. It requires organization that reflects this seriousness, intense political debate, and effective structures.

Feminists in Turkey, feminists in Kurdistan, and the women’s movement as a whole have already begun to take steps that reflect this seriousness. As the Zapatistas say, they have ‘hurried slowly,’ revisiting global experiences, critically evaluating the past, and defining a political direction suited to the needs of the new period. They are building networks to strengthen international ties and, most importantly, they aim to transform both today and tomorrow.

Wherever this process may lead, the women’s peace movement carries the confidence that this partnership in struggle will continue."