Ministry of Interior rejects to disclose Sheikh Said's burial site

The Turkish Ministry of Interior has rejected an application for the disclosure of the burial sites of Sheikh Said and his 47 companions.

The Turkish Ministry of Interior has rejected an application for the disclosure of the burial sites of Sheikh Said and his 47 companions.

The Turkish Ministry of Interior has rejected an application submitted by the Diyarbakir Bar Association, the Sheikh Said Association and one of Said's grandchildren, Kasım Fırat, to disclose the burial sites of Sheikh Said and his 47 companions. The ministry did not respond to the application made on February 15 within 30 days, which is the legal time limit.

Since the application was not answered within the legal time limit, which legally means tacit rejection, the applicants have turned to the Ankara Administrative Tribunal for the stay of execution against tacit rejection.

BACKGROUND

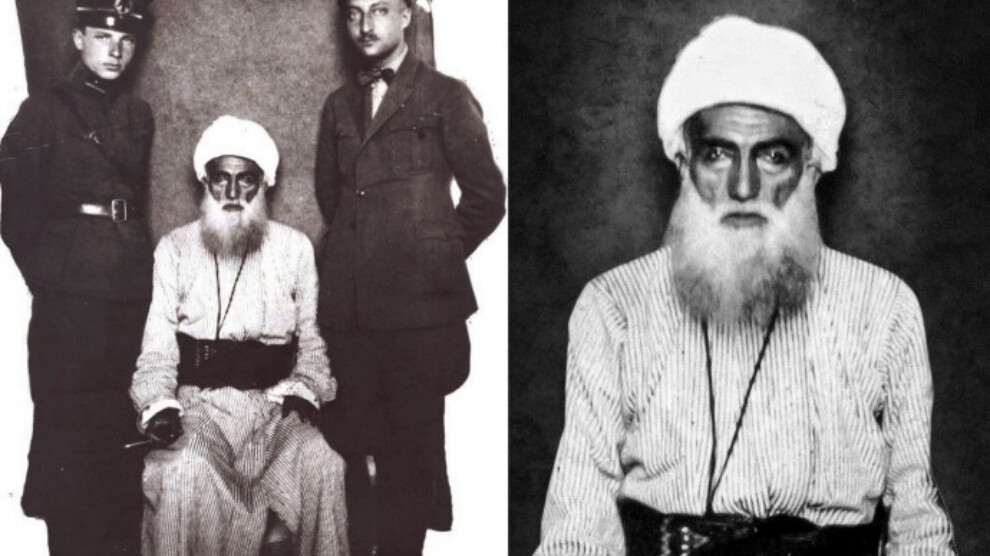

97 years ago, Şêx Seîdê Pîran and 47 companions who led an uprising against the violent policies of the Turkish Republic were publicly hanged. Their burial place is kept secret until today.

The rebellion started under the leadership of the Kurdish-Sunni clergyman Şêx Seîdê Pîran (Sheikh Said) on 13 February 1925 in the village of Pîran in Eğil district of Amed (Diyarbakir) paved the way for numerous Kurdish rebellions after the end of World War I, which followed the process of the Turkish nation-state formation after the fall of the Ottoman Empire and were directed against the denial of the Kurdish existence, the entry of political autonomy and the fascist policy of Turkification. Besides Amed, the uprising also included the regions of Elazığ and Bingöl, and in the further course, the uprising expanded to almost the entire area populated by Kurds in present-day Turkey.

A few weeks later, on 26 March 1925, Turkish military units began air and ground attacks on suspected retreat sites of Kurdish insurgents, after 25,000 soldiers had initially been transferred to the region. At the beginning of April, the number of troops reached about 52,000 men: the insurgency was crushed in blood. At least 15,000 people were killed. At the end of April, Şêx Seîd and a large number of his comrades-in-arms were captured in Muş. A brother-in-law of the cleric who had served as an officer in the Ottoman Empire had betrayed them. After their transfer to Amed, Şêx Seîd and 47 of his companions were sentenced to death on June 28, 1925. The public execution followed one day later. Their burial place is kept secret until today.

Şêx Seîd and his companions were executed, but the Ararat uprisings began the following May. At that time, however, the Turkish government had already established its systematic approach to the Kurdish resistance with its "Reform Plan for the East" (Şark Islahat Planı). Under the cloak of a state of emergency, this plan provided for assimilation measures, including deportations, resettlements and mass murders. With this plan, the Kurdish question was subordinated to the military, which is still noticeable in the near present. What we call the Kurdish question today was created during those years.