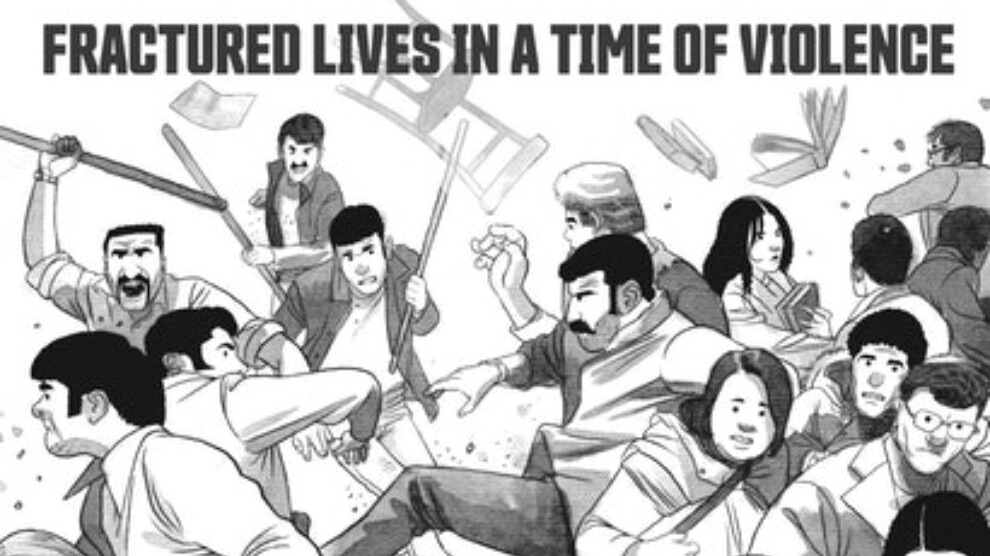

Fractured History, Colorful Lives - A review of the graphic novel 'Turkish Kaleidoscope'

Reimar Heider reviews the graphic novel 'Turkish Kaleidoscope: Fractured Lives in a Time of Violence'.

Reimar Heider reviews the graphic novel 'Turkish Kaleidoscope: Fractured Lives in a Time of Violence'.

Jenny White, social anthropologist and professor for Turkish Studies in Stockholm, studied at Hacettepe University in Ankara during the mid-1970’s and was witness to the violent clashes between revolutionaries and fascists in the years before the 1980 military coup in Turkey. Having spent several months at another university in Turkey roughly 20 years later and having a keen interest in graphic novels, I was curious how “Turkish Kaleidoscope. Fractured Lives in a Time of Violence” would turn out.

The topic as well as its execution in “Turkish Kaleidoscope” is unusual, which makes it even more interesting. I read the book practically in one go because the story was really gripping and well presented. Out of own experiences and interviews with contemporary witnesses, White distills the intertwined stories of several fictionalized persons on the left and on the right. The artist Ergün Gündüz uses a clear drawing style in black and white with occasional color highlights. Some of the characters seem to hint at prominent leftist figures like Deniz Gezmiş (who is never mentioned) and maybe Sakine Cansız, which adds a nice touch.

The strength, but also the main weaknesses of the novel are determined by the narrative choices White makes. In the introduction she notes she wants to “reflect the voices and experiences of ordinary people as much as movement leaders, and those on the right as well as the left.” On that promise, she does not exactly deliver. We don’t see any movement leaders on the left with the exception of one local group leader (who I didn’t recognize), which is strange given the massive presence of certain personalities for the revolutionary movements of the time. On the other hand, MHP leader Alparslan Türkeş has a prominent appearance, although his name is not mentioned. She focuses not on life-long activists or on long-term developments, but on a short timespan and what she calls “ordinary people” on the left and on the right whose lives are often indeed fractured. People get wounded, killed, lose their convictions. The politically most naive seem to have drawn the best lot. That makes for dramatic and interesting stories, and the characters are without exception interesting and compelling.

The political background in front of which the stories unfold, however, remains unnecessarily vague. The choices the individual characters make appear either determined by their upbringing or random and arbitrary. The fragmentation on the left was obviously a problem in those years, and the ideological differences may have been exaggerated. But to leave the socio-economic situation of the country as well as the world situation (cold war, Vietnam, oil crisis) out of the picture makes the political conflicts look like a completely absurd theater.

Striking is the almost complete absence of the Kurdish question in the main story, but also in the present-time epilogue. The word “Kurdish” is mentioned exactly twice, on page 111, before the words “THE END” appear on page 114. And even there it is partially mentioned to downplay Kurdishness: “My mother still speaks only Kurdish. (…) No one cared that we were Kurds, we were poor, that’s all.” (p. 111)

There is a two-page epilogue, called “Reflections” in which we suddenly learn that in the 2010’s there is a “Turkish army’s crackdown on Kurdish civilian areas in the Southeast” and literally only the very last sentence in the whole book mentions the PKK, stating that “the Turkish military is fighting the PKK in the Southeast.”

Obviously the author decided to leave the whole “Kurdish issue” or “Kurdish question” out of the story. She is aware of the importance of the whole complex, and therefore mentions it in the introduction. Incidentally, in exactly those years that the story spans, the foundations of the PKK were laid in the nearby University of Ankara, only a few kilometers away.

To me, this omission is especially saddening because the storytelling is actually great. The graphic execution is almost flawless with a good use of color. The story has a good pacing, the characters are interesting and the novel keeps the tension without getting too confusing despite the many storylines. Eventually all of them are cut off: people leave their organizations or change places. Only Mehmet, the electrician, and Ali, the bakery worker, seem to enjoy come constancy in life—they didn’t get involved in politics.

The concluding “Reflections” which serve as a kind of epilogue are an interesting device, but don’t work very well because the next generation’s stories appear too disconnected if you don’t know your way around in Turkey’s history very well. A written epilogue would have been more useful to contextualize the story. For instance: I don’t think the author sympathizes with the military coup with its massive violent consequences for millions of people. But by leaving these dramatic consequences out of the story, one might get the impression that the coup was justified and necessary to stop the violence and the “madness” that was going on.

For a graphic novel that deals with politics, TURKISH KALEIDOSCOPE is strangely apolitical. It sheds an interesting light on an episode in the past that is still crucial for an understanding of today’s Turkey. But it does so in a way that it hides many of the actual political issues at hand in favor of a personalized version of history that is so common in today’s journalism.

I would be delighted to see one or several sequels to this, dealing with all the issues that were left out of this volume or only mentioned in the all-text introduction: Kemalism, the ban on Kurdish language, the struggle for Kurdish self-determination, extrajudicial killings of opposition members, forced disappearances, the rise of Islamist parties, Alevis, and eventually the inclusive policies on the left that paved the way for the Gezi uprising. I am sure Jenny White has more interviews in store and more stories to tell that connect the past and present.

I recommend the book to every person interested in the clashes between revolutionaries and fascists in 1970’s Turkey as well as to fans of graphic novels. If you already have a good knowledge of those years, that’s definitely a plus, if not, this book may be a good place to start your research on it. Unfortunately it’s very much a Turkish kaleidoscope and not a kaleidoscope of Turkey.

Source: Kleine Kurdistan Kolumne