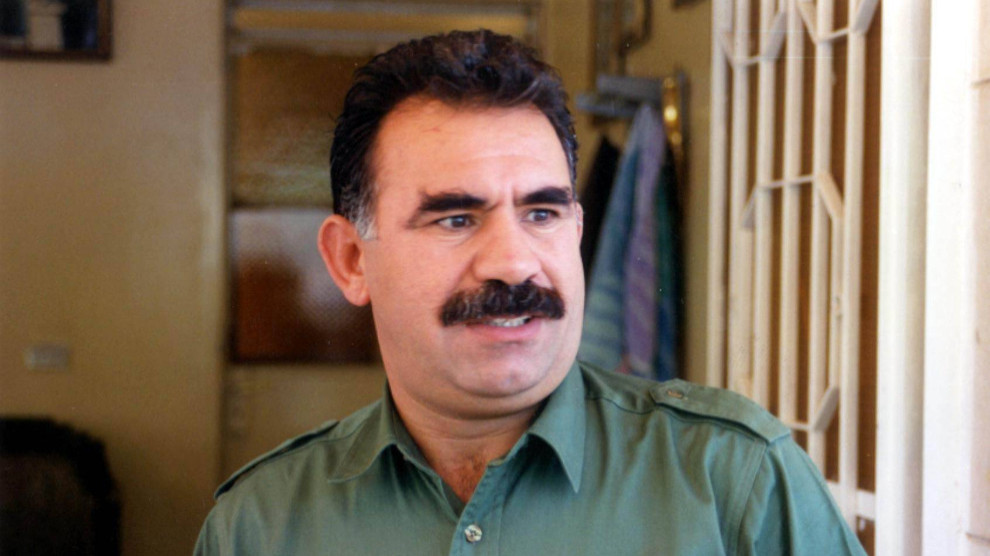

Once expelled from Syria on 9 October 1998, Abdullah Öcalan decided to make his way to Europe rather than to the PKK's strongholds in the Kurdish mountains of Northern Iraq or North-Western Iran.

In an interview with Reuters News Agency, he explained his motivation in doing so in the following terms:

"I am positive that if a political settlement to the [Kurdish] question gains some degree of acceptance, all violence in Turkey, irrespective of from whom it originates, and definitely including the guerrilla warfare, can be halted to a large extent. [...] A process of political dialogue, once initiated, can be transformed into a strategic approach. What does that depend on? If Europe uses its weight, if the USA are supportive and if Turkey is prepared for a political settlement, then we shall definitely prefer to consider such a settlement as our strategic prospective since that is what we want in any event. So it is not correct to say that I came to Europe to escape adverse conditions. Really, if we can only grasp a chance for such a solution, a process of [purely] political struggle can be initiated."

Similar views were expressed by Abdullah Öcalan in an interview conducted with him by the magazine Middle East Review in January 1999:

"There can be no doubt that once the international community has acknowledged the Kurdish question, this will more than anything else result in diplomatic recognition and accordingly my priority is that a dialogue with the Turkish Republic be established in conjunction with internal efforts towards a political settlement. I would like to reiterate what I said about a solution within the existing boundaries of Turkey and the democratic structure of the state. I would like to concentrate on finding a solution to the Kurdish question based on a pluralist concept of democracy. And I shall put emphasis on attempts to get the support both of Turkey and of international democratic powers."

Abdullah Öcalan's first destination was Greece, from where he immediately had to continue to Moscow. Neither of the countries were prepared to effectively grant him political asylum. On 13 November 1998, Abdullah Öcalan entered Italy, where he was allocated temporary accomodation in a Roman suburb until 17 January. The Italian authorities turned down a Turkish request for extradition on grounds that Mr. Öcalan would face the death penalty upon his return to Turkey. At the same time, the German Federal authorities decided to defer an arrest warrant against Abdullah Öcalan that had been issued in 1990 on grounds of a legally adventurous construct. The two countries' prime ministers conferred on possible venues for an international conference on a political solution to the Kurdish question with European involvement.

Mr. Öcalan, in turn, expressed his belief in the basic principles and democratic safeguards of the European Union. For example, his statement to the exile publication Özgür Politika on 16 January 1999 is worded as follows:

"I believe that a concept of law as expressed in the legal framework of the European Union should be developed for the Kurdish question and I have expressed according demands. I wish to underline [our demand] that a legal commission founded on the principles of the European Union should go on fact-finding and research missions in Kurdistan and, if necessary, an international court should be established."

Mr. Öcalan repeatedly made clear that he was prepared to stand trial before such an international court himself under the sole condition that Turkey be tried, too. But his hopes and demands were not met. The Turkish government and media apparatus had unleashed an ever-mounting campaign of chauvinist outrage against Italy for harbouring Öcalan, "the baby killer and murderer of 30,000 people." The campaign amounted to a boycott of Italian products and generated stark anti-Italian sentiments amongst the Turkish populace.

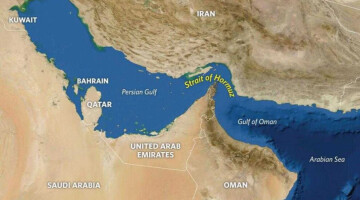

At the same time, and less parochially, the USA silently used diplomatic channels to dissuade European governments from supporting any political initiative for a peaceful resolution of the Kurdish conflict. Germany's move to defer the arrest warrant then turned out to be a green light for the Italian government's final decision to pressure Abdullah Öcalan into leaving the country for an uncertain destination notwithstanding his outstanding asylum application. All European countries refused to grant him leave to enter. Via Moscow, Athens and Corfu the Kurdish leader was finally flown to the Greek Embassy at Nairobi, Kenya, in what became increasingly obvious as a deliberate consipracy to maneuvre him into a position where he could be handed over to the Turkish authorities as soon as safeguards of European law were effectively by-passed.

In their pending application to the European Court of Human Rights, Abdullah Öcalan's legal representatives have shown that the conspiracy leading to his abduction involved unlawful conduct on the part of either the authorities or at least unauthorised officers of Greece, Russia, Italy and Kenya, while there are strong indications that Germany, Britain, the Netherlands and Israel were at least indirectly involved at some stage of the operation.

When Mr. Öcalan was finally forced off the premises of the Greek Embassy at Nairobi on 15 February 1999, the private plane of a Turkish businessman (who, most notably, was extradited from the USA to Turkey on serious charges of off-shore banking and tax crimes in summer 2001) had already been waiting on the tarmac of Nairobi airport for a couple of days.

In his application to the European Court of Human Rights, Mr. Öcalan gave an account of the last sequence of events surrounding his abduction:

"Black persons in a jeep kidnapped me by force. Staying in the embassy or going with them could have resulted in my being killed all the same. They drove the car right up to the door of the plane. Later, we entered a non-public area of the airport. My consciousness failed me. Most probably they used some drugs on me. I can confirm that I was not in the possession of my will power at that stage. I can confirm that I felt numb.

As soon as I entered the plane someone hurled on me. They were Turkish. All those standing around the plane were armed and from their appearance I think they were either US Americans or Israelis. No Turks were there until we got to the plane. Turks were only on the plane itself."

Source: International Initiative Freedom For Abdullah Ocalan